|

Olympus E-M1: the Full Monty The First and Second Look, and Then Some |

|

My other articles related to the |

|

My other articles on the E-M1:

|

|

So, here is the much-anticipated E-M1 from Olympus, a semi-pro (or advanced-amateur) camera, the second one in the OM-D line, aimed at persuading die-hard SLR users (like myself) that they don't really need an SLR to enjoy photography the way they're used to.

Was the mission a success? The E-M5 from 2012 was almost there; I bought it and have no regrets, and I've been using it for 18 months or so, with good results and, what is equally important, the way I like using a camera. Now comes the bigger brother, offering better handling, luxurious make and finish, and, last but not least, a full autofocus compatibility with Four Thirds lenses. To ease the suspense, let me state right away: I think Olympus engineers achieved the goals they've set up; for details what went right (and what not quite right, if close), read on. |

.t.jpg)

Here shown with the 12-40mm/2.8 MZD lens (All images © by Olympus) |

|

Micro Four Thirds The Micro Four Thirds (of just μFT) is the standard, developed by Olympus and Panasonic, defining the sensor size, lens mount, and lens-to-camera interface, so that cameras and lenses conforming to it are guaranteed to work together. It is intended for cameras not using an internal mirror for optical viewing, therefore the lens-to-image distance in μFT is smaller than in the original Four Thirds (or FT) standard, used for (mostly) Olympus SLRs, now extinct. Four Thirds lenses can be mounted on μFT bodies with an appropriate adapter, and the autoexposure will work properly, but (until the E-M1, read on), the autofocus will not. The opposite is not true: μFT lenses cannot be mounted on FT bodies. The μFT imager size is the same as in Four Thirds: 13×17.3 mm, it is a bit smaller than the common APS-C format (14.8×22.2 mm); much smaller than the so-called full frame (24×36 mm), but much larger than the common 1/1.7" sensor used in better compacts (5.7×7.6 mm). The sensor size issues are discussed in a separate article. Body, make and finish The first, casual inspection of the E-M1 leaves very good impression, indeed. The camera, while still very small (as compared to a DSLR, that is) is a bit bigger and heavier than its E-M5 junior sibling, just big enough to provide better handling, while still being fairly compact. Let me show some numbers, comparing the body size and weight of the E-M1 with its immediate predecessor, but also with the smallest DSLR from the Olympus E-series, the E-420, and with the compact, but full-featured, E-620 I'm still using. (I'm showing the size as W×H, as the body depth is not really relevant; it is the lens which really defines that dimension. The weight includes battery and memory card.)

As I liked the ergonomics of the E-620 a lot, I found the E-M1 just the right size and weight for my average-sized hands; if your hands are larger, you may find it a bit too small. What additionally helps here is a prominent grip, one of the better ones I've experienced in a camera of this size. The camera looks busy, but not confusingly so; the black matte finish is flawless. The body interior shell is made of magnesium alloy, strong and rigid enough to provide enough of dimensional stability. Now, this being the current flagship of Olympus μFT cameras, the E-M1 has the proper gasketing to assure that it remains dust- and splash-proof; some lenses (most notably: the 12-40 mm MZD shown above and the 12-50 mm I've been using for the last 18 months) also provide this feature. Olympus also claims that the camera is freeze-proof down to -10°C (that's 14°F for the non-metric crowd); I am not sure if this is a serious claim: how would the battery perform at this point? Anyway, the body design, make, and finish are first-class, leaving nothing to be desired. Viewfinder The viewfinder, for those who spent the last few years under a stone, is electronic; what looks like a traditional pentaprism hump is actually a device to look at a miniature high-resolution monitor panel inside. It is the same Epson Ultimicron XGA panel as the one used in the VF-4 viewfinder, released for the E-P5 of the Pen series by Olympus (also used in a few other makers' cameras since). It has a resolution of 2.36 million single-component dots, corresponding to 767 thousand RGB pixels, which is almost exactly the resolution of an XGA computer screen. This is an improvement from the 1.44 million dots (480 thousand pixels) in the E-M5, which is the SVGA screen resolution. While the finder in the E-M5 was already usable, the new one is just gorgeous, especially with the fast refresh rate which makes it virtually smear-proof (no streaks at rapid camera or subject movements). The finder magnification is most impressive: nominal 1.48× which is not really a meaningful value when comparing cameras of varying sensor sizes; for a comparison each quoted value should be divided by the appropriate focal length multiplier (2.0 for FT/μFT, 1.6 for cameras using APS-C sensors). Anyway, this is much larger than 1.15× in the E-3/E-5 or E-M5. Actually, very few DSLRs on the market offer a larger viewing area, and at most by a few percent. Thus, let me make an official statement, to revoke anything I might have said before on this subject: I, Andrzej Wrotniak, hereby declare for all who care to hear that I no longer need an optical, SLR viewing system, and I am now willing to live with electronic viewfinders as long as they are as good as, or better than, the one used in the E-M5. The viewfinder can be switched between (basically) two different modes, with the exposure information either overlaid over the full-screen image preview, or with the preview somewhat reduced in size, and that information shown in a separate bar below it. If you use the 3:2 (or higher) aspect ratio, the image is not even reduced, it still uses the full finder width, just moved up away from the information display, nice. And, with electronic viewing, setting the aspect ratio at shooting finally makes sense: in SLR finders there was no way to check the image composition. Actually, even in the 4:3 aspect I tend to keep the info display off the viewing area, trading off a bit in magnification. The image is still impressively large, and there are fewer distractions; possibly just a matter of taste. In a welcome development, the camera has a finder proximity sensor: the finder is turned off when you remove your eye from it (and the monitor screen is disabled when you are using the eyepiece). An energy-saving measure, also reducing the annoyance factor. Anyway (putting aside full compatibility with E-System lenses) the EVF is, from where I stand, the greatest selling point of the new camera. Try it once, and you will be hooked. External monitor

This is a very nice monitor, with the resolution upgraded to 1.04 million dots, up from

The screen resolution improvement will be more visible for those coming directly from E-System SLRs, which were limited to It can be tilted up and down, but not swiveled to the side (or backwards). I don't consider this a limitation (never having a need to use this feature in the portrait orientation), and the tilt-only design is more compact in use (no extra room needed to the left of camera). | |

|

The main reason that mirror-less cameras (MILCs) did not overtake the SLRs sooner was the AF accuracy and speed, where phase-detection systems (used in SLRs) originally had a clear advantage over contrast-detection ones (these use the imager, therefore they are more suitable for MILCs). Here is a brief remainder on how both systems work.

Olympus (E-510) and Canon (D1 Mk. III) were first on the market with a dual viewing and AF system: in addition to the typical SLR approach (optical viewing, phase-detect focusing with dedicated sensors), you could switch to the Live View mode, with electronic preview on the external monitor and contrast-detect AF done with the imager. I'm skipping here partial solutions used by Sony and Olympus in some earlier models, and some of the more recent Sony Alpha non-SLRs using pure electronic viewing, but with a full-time, semi-transparent mirror redirecting some light to dedicated PD AF sensors. See also a section on that in my original E-510 review from 2007, and It's all Done with Mirrors, about the hybrid solution in the Olympus E-330. The main problem with dual (SLR and LV) viewing systems was that each AF approach needs a different lens servo mechanism design. While it is possible to design a lens working OK with both systems, a lens developed for a phase-detection AF will not work well on a contrast-detection body. This is while Live View in Olympus SLRs would switch back to the "SLR mode" for the final AF operation just before exposure, with a whole circus of movement, noise, and related activity. Olympus released a few lenses supporting both AF modes; for the other (often excellent and costly) Digital Zuikos the AF performance was either bad, or very bad, or just nonexistent when used on μFT bodies, with no PD AF to fall back to. Therefore, in order to attract the former SLR users — many of them, like myself, quite enthusiastic about the Olympus E-System, and with some investment in Four Thirds Lenses, Olympus engineers faced two challenges:

The first problem has been solved (by a number of camera makers, not just Olympus) a year or two ago: the accuracy and speed of CD AF systems became at least comparable (and often better than) in the PD AF systems, used in SLRs. In case of Olympus cameras, the latest Pens (and, most notably, the E-M5) leave nothing here to be desired — as long as lenses developed specifically for the μFT system are being used. There is one exception to the above: contrast-detection AF does not usually perform too good in the continuous and/or focus-tracking mode. I'm not technically fluent enough in the subject to tell why. The second issue has been addressed by Olympus just recently, and in a quite radical way: by adding a full-fledged phase detection AF functionality, using the imager itself. More exactly, some imager photosites have been relieved of their imaging duty and devoted entirely to collecting AF information (there must be reasons why the same photosite cannot do both). The E-M1 is the first Olympus camera using this approach. Other manufacturers are introducing similar solutions; Fujifilm, Canon, and Nikon all implemented some flavor of imager-based PD AF similar to what Olympus does; looks like the devil is in details, though. |

|

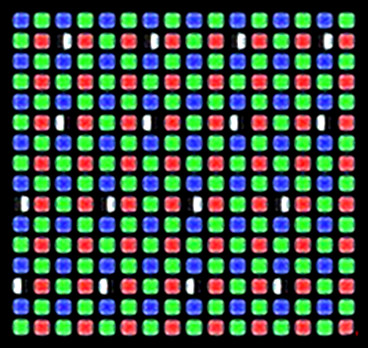

In the new (proprietary?) sensor, a standard Bayer matrix of photosites covered by Red, Green, and Blue filters (and therefore responsive to a given component of visible light) has been slightly modified: 12.5% of the Green photosites (one in eight) are reassigned from the image-recording process to PD AF functionality. Obviously, the green filter is no longer needed for those photosites, so it has been removed (more than tripling their responsiveness to visible light), and the missing information is reconstructed by interpolation from the nearest neighbors. Luckily, in the Bayer scheme 50% of photosites are Green, with 25% each assigned to the other two primary colors, so there is plenty left to interpolate from. |

|

|

There is — must be! — some unavoidable information loss: after all, we suddenly have 6.25% of effectively dead pixels, and this must affect the image detail, but I really wouldn't worry about that. What happens is basically close to drawing the image information from a 15-megapixel sensor instead of 16-megapixel one. One thing which remains unclear is whether the disabled Green photosites are limited to the central part of the frame (corresponding to the extent of the 37-point, central phase-detection AF area), or if they cover the full frame. My gut feeling is the latter. (If I am wrong, though, the information loss is less than the 6.25% mentioned above.) Unfortunately, I have no idea who is the manufacturer of the new sensor, and Olympus keeps a secrecy on the subject, except for admitting some participation in the design process. It is possible (just possible!) that this may mean the end of the long stretch (since 2005) of using imagers made by Panasonic, and a promise of new, strange and wonderful, things to come... | |

|

The bottom line of all that is that new camera has a new, 16-megapixel sensor (effectively downgraded slightly to 15 MP), and a new AF system, referred to as Dual Fast AF. The camera detects the lens mounted, and then uses one or two AF methods:

As we can see, PD AF has been introduced not just for the sake of legacy FT lenses; it was also put to a good use with the μFT ones. How does it translate into real-life AF experience with the camera? Here are my impressions, based on a very informal experiment with a set of lenses and camera bodies:

Anyway, this means that what Olympus claims is true: the FT lenses behave on the E-M1 equally well as on cameras for which they were originally designed. This means I can still use two lenses I want to keep from my E-Series stable: the 12-60 mm and 50 mm Macro; the others may depart into a dignified retirement. To close the chapter on autofocus, the AF pattern and its location can be easily modified (especially when you customize the controls with that in mind), and the camera can be also set up to autofocus on demand, i.e. with AF disabled but performed on a press of the Lock button; especially useful for critical applications. Last but not least, this may be the first digital camera which I can really use with manually focused lenses. It can be set up to show a highly magnified frame fragment during manual focusing, using peaking (highlighting) to detect contours which are in focus. This would be not easy, if at all possible. to implement on an SLR (unless you're using the Live View, when it becomes a non-SLR). Lenses A camera of this type needs a range of quality lenses, otherwise its attractiveness suffers. Olympus and Panasonic started making ILCs (non-SLR, interchangeable lens cameras), well before other brands joined the game, so at this moment they offer the widest choice for cameras of this class: more than twenty lenses, with a healthy share of quality primes. So far all lenses I'm using with the E-M1 are by Olympus and they are, as I expected, exemplary performers. I will be, however, getting at least one lens by Panasonic: the 7-14 mm to cover my wide-end needs. It is in the lens division where, actually, the size/weight advantages of the μFT standard show most. I'm sometimes amazed at the focal length range I can now carry in a compact camera bag. Being able to use Four Thirds lenses on the E-M1 with full AF functionality is a big plus, but only for those who invested in that lens system, I wouldn't recommend buying them now, just to be used with that camera. The compactness and AF performance of the μFT line tip the scales heavily here. Other specs and features This will be a quick list, as the most important issues have been already covered. The list is arranged in no particular order.

|

|

|

E-M1 in Use A precondition to enjoying the E-M1 is setting up the camera's options and controls to your needs and taste. This took me a whole day; in the process I wrote, for my own use, an HTML document with all settings the way I like them. Generally, I found the E-M1 very much to my liking in handling and operation. Just the right size, very well balanced with all lenses I've tried it with (including the 12-40 mm F/8 and 75 mm F/1.8), positive controls and secure grip — all of this adds up to a most enjoyable experience. The only inconvenience is that the arrow cluster in the back is a bit too small for my liking; another 2 mm across (there is room left!) would help a lot. Cosmetically I consider the E-M1 to be really pretty; don't understand people complaining about its "ugliness". Are we talking about the same camera? It may be a matter of taste, but esthetically I prefer when the form is defined by function (or at least pretends to) rather than the other way around. And yes, there is a resemblance to the legendary OM-1, clearly intentional. And the thing just oozes quality. Using the electronic viewfinder in this camera is a real delight. Epson came up here with a real winner, setting a new mark to beat, and Olympus finished the job very nicely. This is the first EVF I can really use instead of SLR viewing. A separate chapter is the autofocus. When used with μFT lenses, this is the fastest, most accurate AF action I have ever experienced. This seems to be confirmed by some reviewers who could compare the E-M1 with cameras by other makers (my own experience is limited to Sony and Canon in addition, of course, to Olympus). With the Four Thirds lenses the AF is, at long last, usable. Not as great as that with μFT lenses (we're getting spoiled fast!), but as good as it was on E-Series SLRs. Before getting the E-M1, I've been using the E-M5 for eighteen months. I really like that camera and I enjoyed it a lot. But now, every time I switch to it after using the E-M1 for a while, it feels like a poor people's camera. I am sorry to say that, but I can't get rid of this feeling, really. At the moment this is a matter of the body feel, viewfinder, and controls. I am not sure I will be able to see a difference between images from both cameras. Actually, I believe both deliver results better than I really need. And the E-M5 body is so small that it will make a competent backup to sit in my bag until it is needed (or until my wife wants to use it; she really likes that camera a lot). Does it deliver? Yes. These may be the best (technically) images I've got from any camera yet. I realize this is a strong statement, but that's how I see it.

Have a closer look at my Samples, Part 1 (before the camera was set up to my liking) and There are also Real-Life Image Samples shot with the MZD 75-300/4.8-6.7, perhaps worth a look. The three series of high-ISO samples show that images at up to up to ISO 6400 are presentable; the progress on this field in the last two or three years is just amazing. Even those shot at ISO 25,600 (das ist 45°DIN, meine deutsche Freunde, unmöglich!) are usable, if not too pretty, very much like ISO 3200 of just four years ago. The close-up and macro performance of the E-M1 is very satisfactory. This really is a matter of the lens, but there is no need to search: the "standard" 12-50 mm F/3.5-6.3 zoom provides a real macro capability up to 1:1 (equivalent) magnification, i.e., a frame 36 mm across.

Conclusions No camera I've known was without flaws, this is real world. It is understandable if the these flaws are a result of technology limitations, or price constraints — these are hard to avoid and should be accepted. It is somewhat more irritating (and less forgivable) if these flaws are a result of (what we consider to be) a bad judgement or bad taste. The E-M1 is a great camera: the best yet digital from Olympus, I dare say, and one of the best ones by anyone. Yet it has a few warts, which feel even more painful as they belong to the second (easily avoidable) group. First, the addition of novelty, toy-like features sometimes interfering with the basic camera functions. Second, an unnecessary complication of some parts of the user interface (the darn lever switch comes to mind!), additionally aggravated by bad English on some option names or on-screen hints, often misleading rather than helping. Third: lackluster battery performance (combined with high cost of spares). These are my bigger complaints, any other points are of secondary importance. The first two points could be addressed as a firmware update, but, I'm afraid to say, don't hold your breath. I've been following Olympus firmware updates for their many cameras for more than ten years now and the general pattern is that these usually address only performance problems and obvious bugs, rarely design issues. I'm afraid we just have take it or leave it. I would really like to be wrong. Warts and all, the E-M1 is a most capable and enjoyable (if a bit overpriced, from where I stand) camera. If you are still a Four Thirds user, this may be a good time to switch, still retaining the full use of your lenses. If you are already into Micro Four Thirds, treat yourself to a new level of performance, functionality, and style. If you are tired or otherwise unhappy with your current Canon or Nikon system, come and see how things can be done. There are many reviews and hands-on reports of the E-M1 available on the Web; here I'm providing links to those which either offer most information or cover aspects not easily found elsewhere. (I am also omitting some articles which are almost unreadable because of the amount of advertising and other unrelated contents in the page layout; sorry, I can't read those.)

|

|

My other articles related to the |

| This page is not sponsored or endorsed by Olympus (or anyone else) and presents solely the views of the author. |

| Home: wrotniak.net | Search this site | Change font size |

| Posted 2013/12/07; last updated 2017/09/04 | Copyright © 2013-2017 by J. Andrzej Wrotniak |