|

Olympus E-510 A Technical Review and Reference |

|

My other articles related to the |

|

This is a detailed, technically-inclined review of (and refeence for) the Olympus E-510 digital SLR. Originally based on the first three weeks of my familiarity with the camera, it was being expanded and refined for about a year. As of this (June, 2008) update, it is basically complete, although I can predict small, occasional touch-ups and additions in the months to come. This is a long article, as it contains explanations of the concepts used, clarifications of the specs, and quite a many, possibly opinionated, comments. Before reading it, you may want to have a look at Class of 2007 (a brief intro to the E-510 and E-410); after — check my E-510 Quick Notes.

|

|

Table of Contents |

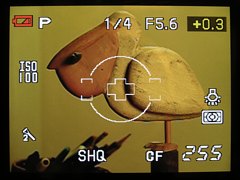

All accompanying images, unless stated otherwise, were shot with the Olympus C-5060WZ in aperture priority, Some other E-510 articles here: | |

|

This is the seventh model in the Olympus E-System line of digital SLRs, based on the Four Thirds standard on the lens/camera interface. The series started with the professional E-1 back in 2003 (a camera which achieved a cult status, still having many dedicated users), followed by the E-300 in 2004, and then, in late 2005, by the popular E-500: inexpensive, but nicely made and capable of delivering first-class results. After the E-500, Olympus released two 2006 models (which were not intended to replace it, but rather to complement the line): the E-330, first live digital preview in an interchangeable-lens dSLR, and the E-400, a transitional model, never sold in the U.S. market. The E-500 became deservedly popular, and brought Olympus dSLR sales up by 40%, but on this market you have to get a "new, improved" model every year: how can a camera delivering good images in 2005 produce equally good ones in 2007? Enter the class of 2007: the non-identical twins, the E-410 and E-510, soon to be followed by the pro-grade model (not named yet). All these have one feature in common, almost new to the Olympus SLR line: live image preview on the LCD monitor. I said "almost", because of the E-330 mentioned above, but that one became, for a number of reasons, rather a niche product, being outsold many times by the E-500. And — lo and behold — this year Canon has introduced live preview in the EOS D1 Mark III ($4500, body only). The new cameras share most of the features and specifications, including the image sensor and the whole image-processing engine (both hardware and firmware) are more than evolutionary, incremental modifications to the E-500 (or E-400). The most important change is the transition from a coupled-charge device (CCD) image sensor used in the previous models to an NMOS one (referred to as Live MOS by the manufacturer). This change was necessitated by the live preview: it looks like CCD sensors are not able of supporting it. That's a pity, because the Kodak KAF line of sensors Olympus used before was excellent; the new NMOS ones have yet to prove themselves. NMOS stands for "negative-channel metal oxide semiconductor" and it is closely related to the more common CMOS (complementary metal oxide semiconductor) sensor type; thanks to Eamon Hickey for this clarification. The differences between the E-410 and E-510 are limited to just three things:

For more, again, refer to my Class of 2007 article. |

|

|

|

Most of these are as claimed by Olympus, if available; if not, other sources (including my own measurements or deductions) are shown; I will be clear if the latter are different than claimed. The official manufacturer's specs can be found here. | |

|

Construction:

Plastic (polycarbonate fiber?), metal inner frame. | Lightweight, but with a solid feel. Rigid enough: tight fit of parts and no flexing. |

|

Finish:

Crinkled black; rubberized grip and thumb rest. |

Somewhat improved from the E-500 (which has a smooth matte finish), but not as good as in the E-300 (where the crinkled surface could be taken for metal). Very nice job overall. |

|

Weatherproofing:

None | Not in this price range, and tough to do in this size/weight category. |

|

Size (WxHxD):

136×92×77 mm |

This is quite small, one of the most compact digital SLRs on the market, but the camera really looks smaller then the numbers would indicate. While you are handling the E-510, it seems significantly smaller than the E-500; putting them side by side (and using a ruler) defies this impression. Actually, this camera is 5.5 mm wider than its predecessor, it is also deeper — due to the thicker grip with a bulge in the lower part. Yes, the body height has been reduced by 2.5 mm, and the controls on the camera's back had to be squeezed a bit in the vertical dimension, but that's it.

Yet, somehow the designers added a sloping curve here, a differently profiled edge there, and achieved this overall effect of the camera being smaller than it really is. Overall, the older E-500 looks more chunky and, I dare say, cuter than the new model. Looks aside, I also like more the way in which the old camera sits in your hands (at least after the first two weeks of using the E-510). One more thing, already mentioned elsewhere: in the E-510, due to the prominent protrusion to the left of the viewfinder, the latter is more centrally located. This leaves most of us non-Japanese sticking our noses into the LCD monitor way too often. I think the older shape is more practical. On the plus side, the thumb rest, in addition to being now padded, is also better profiled, which makes accidental pressing of the Function button (Reference WB in the E-500) less likely. |

|

Weight (body):

460 g |

This, counted without a battery or memory cards, is fairly low, if a tad (25 g, or just about one ounce) more than the E-500. Still, the E-510 remains one of the lightest bodies among digital SLRs:

The BLM-1 battery will add an extra 75 g, and, if you have to know, a CF card — another 8-12 g, to the total of about 545 g. Fortunately, in spite of the low weight the camera feels solid; certainly more so than, for example, the Digital Rebel XTi, i.e., Canon 400D. For a comparison, here are weights of some competing models of the same vintage:

As we can see, the body-plus-battery weight of the E-510 is almost the same as of the similar Canon and Nikon models; the only camera standing out in this respect is the E-410. The size and weight advantages of the E-510 (not to mention its smaller sibling) become visible only when you add lenses into the equation. The battery weight and capacity will be discussed in the power section. |

|

Lens mount:

Four Thirds standard |

This is a standard, specifying the sensor size and lens mount, including the backfocus length (distance between the lens flange and image sensor), as well as the mechanical and electronic coupling to the camera. The standard is open, but so far only Olympus and Panasonic make cameras following it (with the sole Panasonic DMC-L1 model also re-branded as Leica Digilux 3).

At this moment Olympus has more lenses available, designed specifically for its digital SLRs, than other manufacturers for their respective APS-C systems. (Yes, those cameras will work with legacy, film-SLR lenses of the same brand or mount, but this is not quite the same, especially for the wide-to-normal optics at full apertures.) There are also two lenses branded by Leica (if you can afford them), and a number of ones by Sigma (of varying quality), which will be fully functional with any Four Thirds body. Because the Four Thirds frame is half of the (linear) size of a 35-mm film one, any lens used on such a body provides the same angular coverage as a lens with twice that focal length on a 35-mm film camera. What is often overlooked, is that while the four Thirds lenses do not have to provide an image circle covering a full 35-mm frame, within their coverage they have to assure twice the resolution, because the image undergoes twice the magnification between the sensor and the final viewed image (print or screen). The full list of Four Thirds lenses is available elsewhere on my site. The Olympus lenses range from inexpensive (still, very respectable), through mid-price (try to match the 50 mm F/2 Macro ZD performance at any price, not just $430!) to some pro-grade, exotically-priced glass (like the 300 mm F/2.8 ZD, at $6000 or so). The mount size (internal diameter) is 46 mm, is huge, especially when compared to the sensor size; actually, it is larger than in most 35-mm film SLRs. There are some good reasons for that, but this is beyond the scope of this article. Besides, other camera makers avoid talking on this subject. |

|

Control coupling:

Electronic |

There is no mechanical coupling between the camera body and lens (except, obviously, for the bayonet fixture to keep the lens attached); a focusing micromotor is built into every lens, and the aperture also responds to electric signals received from the body. Each lens has its own microprocessor, running its own firmware, which can be updated from the camera.

The zoom control is, like in all digital SLRs, mechanical, and this is much more precise than any electronic adjustment by controls on camera's body or by a "fly by wire" lens ring. I've seen gossip about the kit lenses using "fly by wire", electronically-coupled zooming in the new "kit" lenses. This is an example of some half-wit spreading irresponsible rumors; anyone can check that just by turning the zoom ring on a lens not connected to the camera. The latter solution is, however, used for manual focusing (at least in all ZD lenses I've seen). Usually I dislike this feature, preferring a mechanically-coupled focus ring, but, as you will see below, this can be done right, as demonstrated by the two new "kit" lenses. |

Bundled lenses:

Both lenses shown to scale (Photos by Olympus) |

Depending on the package, the camera can come with both these lenses, or just the first one, or with none. (I am not sure if the 17.5-45 mm, F/3.5-5.6 ZD is available on some markets). The lenses are priced very competitively, increasing the cost of the package by only $100 or so apiece, so that the 2-lens kit becomes an obvious choice, even if you already have a bag (drawer?) full of Zuiko Digital optics.

Both these lenses were originally introduced with the E-400, bot that camera was never available on the North American market, so they are actually just debuting in the U.S. They deserve a separate article, so here are just the first impressions. First of all, these lenses are incredibly small and lightweight:

To make the comparison more honest, we have to notice that the new "tele" zoom is not as bright as the old one; the difference is about 1/3 EV at the short end, and 2/3 EV at the long one (this corresponds to required shutter speeds longer by 26% and 60%, respectively, if the aperture values are accurate). Still, we are talking about 300 mm EFL (Equivalent Focal Length), providing the same image angle as a 300 mm lens on a full-frame 35-mm film camera! Compared to that, the 3 mm lost at the long end of the shorter lens are pocket change. What I consider most important here that Olympus kept the 14 mm (28 mm EFL) wide angle end in the new lens, not choosing the easy way to rise it to 30 or, blasphemy, 35 mm EFL (15 or 17.5 mm actual value). Both new lenses together weigh less than the older 40-150 mm alone (or, for that matter, the 14-54 mm F/2.8-3.5 ZD, my favorite "standard" zoom), and this makes them ideal companions for traveling light or hiking. Nothing, however, comes free. To trim the weight, Olympus engineers had to reduce the use of metal in these lenses, up to using plastic lens mounts. While something makes me to abhor this very idea, I understand the reasons behind it: attaching a metal bayonet to a totally plastic construction would only move the point of mechanical vulnerability from the bayonet itself to the screws securing it to the rest of the lens. Anyway, only time will tell how does the plastic mount affect long-term reliability and precision of these lenses. To be impartial: almost all other manufacturers (except for Pentax) have been using plastic mounts in their "kit" lenses for a few years already; Olympus was, as far as I know, the next-to-last Mohican. The letters "ED" in lens designation stand for using special glass in the lens design (low dispersion, extra-low dispersion, or high refraction, which achieves the same goal). This allows for better correction of various optical flaws, especially important under the size and weigh restraints Olympus designers imposed upon themselves. The downside is that the solution costs extra money, as do aspherical elements, introduced for the same purpose. The 14-42 mm ZD ED has two aspherical elements and one made of ED glass; quite unusual in a "kit" lens; the 40-150 mm ZD ED sports one ED element. To me, it shows Olympus is serious about image quality in these lenses, there is no "they won't need that" attitude. We also do not know what, if any, is the use of molded synthetics in lens elements. This may affect, in the long run again, optical quality. If any of the Readers has any information of that, please let me know. Now the good news. So far both lenses seem to perform very nicely, better than I ever expected and visibly better than the "old" kit lenses. (Since the original posting of this review I was able to do a detailed comparison, and had to upgrade my opinion on the "new" 40-150 mm.) Surprisingly, it is in these two cheap lenses where Olympus finally got it right with the "fly by wire" manual focus ring. I was unhappy with how this was implemented in all previous ZD lenses I've tried; now it is close to perfect: precise, with just the right amount of dampening action, no disengagement between the movement of your hand and what the lens is doing. An impressive job, although I'm still missing some tactile feedback when either end of the focusing range is reached. Obviously, this is important only if you perform any manual focusing; I rarely do that, and most of the camera buyers never will (although I bet many will occasionally switch to the MF by accident). Small pleasures of life: have you ever tried to put on, or take off, the lens cap with the hood mounted on? I've been complaining about Olympus caps since 2001 (E-10). After just six years, Olympus got this 50-cent accessory right: the new caps allow to do that easily; no longer do I have to buy replacements (very nice ones, by the way) by Tamron. Oh, and a replacement cap is no longer priced at a ridiculous $15; the new price of $7 is more reasonable. Overall, an excellent job with the kit lenses; the old ones were better than anyone else's, and these seem to deliver even better results, with the extra bonus of reduced weight and size. The only real lens tests published nowadays are those by Popular Photography (see here how I read them); everybody else measures the combined resolution of the lens and camera; that is usually affected by the settings used. In the E-510 this combined resolution is brought down, as you will see, by the default setting of the noise filter, so it does not really reflect the capabilities of the lens itself. The first time I saw some images done with the 14-42 mm, and noise filtering disabled, my jaw dropped down. This is consistent with the Popular Photography test of this lens. |

|

Using legacy lenses:

Yes, with adapter |

Four Thirds cameras give you unmatched flexibility in using legacy lenses, i.e., ones designed for other SLRs, especially film ones. This is because the distance between the lens flange and the sensor is 3 to 7 mm shorter than for any other SLR system I'm aware of, leaving enough room for a mount adapter to be fitted.

Yes, you will need an adapter for every lens mount you want to use, but these do not have to cost you $200 like some; a number of vendors on eBay are offering them at reasonable prices. You also have to focus by hand, even without the benefit of focus confirmation, and autoexposure is possible only in the aperture priority mode, after the aperture is closed by hand to the working value. Even then, metering suffers from some anomalies, see here. The original limitation disallowing to use image stabilization with such lenses has been addressed in the firmware update from January, 2008. On the other hand, you can find many lenses, especially those of long focal length, which will be capable of providing the larger resolution needed for the Four Thirds frame size (remember, they were designed for film cameras, with resolution needs twice as low), and those lenses can be attractively priced. While I'm not overly enthusiastic about using legacy lenses on Olympus bodies (manual focusing in the small viewfinder), many people remain undeterred, and with very good results. If you are interested, refer to my legacy lens article for some basic information and links for further reading. |

|

Sensor type:

Live MOS |

This is just a fancy name for an NMOS sensor, made by Panasonic, used in this camera. It just goes well with Live View, but really means nothing. Olympus is not disclosing the actual sensor designation, or its specifications. Now, for me the transition from Kodak KAF-series CCD sensors to NMOS is perhaps the biggest change between this model and the older E-500, E-300, and E-1. The Kodak sensors were nothing short of excellent, and the Live MOS ones remain a big unknown. As far as I understand, CCDs have a higher dynamic range and lower intrinsic noise value. On the other hand, MOS units are easier to pick-up and process the signal from, and that's why some manufacturers are moving over to them, a trend, in the SLR domain at least, started by Canon a few years ago. My intuition says that it is preferable to start from a better initial information, and keep the amount of signal cleanup as low as possible, and this is why I always was a believer in CCD sensors. In practice, things may turn either way. The proof will be in the pictures. There is a small article on Live MOS on Panasonic's Web site. Interestingly, Panasonic claims that the Live MOS offers the receptor ratio of 50%, as compared to 35% in CMOS sensors. While the concept is not defined in the article (after all, all Panasonic buyers know those things!), I understand it as the fraction of the total sensor area which is photosensitive. And then things become interesting: this means that, in spite of slightly (13%) smaller pixel pitch (distance between photosites), the Live MOS offers a photosite size larger than a CMOS sensor: by about 10% linear, or 20% in terms of the area. While I consider this insignificant, this is a recommended reading to those who claim that Four Thirds sensors cannot compete with APS-C ones because of "small pixels". |

|

Effective sensor size:

17.3×13.0 mm |

That size is a part of the Four Thirds standard. This is twice the linear size of the largest (2/3" nominal) sensors used, with very few exceptions, in better non-SLR cameras, and half of the 35-mm film frame size.

This is, for all practical purposes, very close to the 22.2×14.8 mm of APS-C sensors used in most digital cameras (some Canon pro models being a sole exception), see my article on sensor sizes. |

|

Pixel count:

Nominal 10 megapixels |

The number of photosites from which the image is recorded is 9.98 million (more exactly: 9,980,928), what, in computer terms, can be expressed as 9.52 "binary" megapixels (where "mega" means 220, or 1.049 million).

This is a lot. Actually, I believe that 5 MP is enough for anything I (or most of us) would be doing. Still, manufacturers are pushing the number up, for a few reasons:

With the precise framing of an SLR viewfinder, many times my images do not need any cropping at all. Quite often, however, an otherwise well-composed picture needs a 5% or so crop to straighten the horizon a bit, or to remove some distracting detail at the frame edge. With ten megapixels to start with, a 10% (linear) crop leaves me still with eight MP. The new Canon professional flagship, EOS 1Ds Mk. III, introduced two months after the E-510, boasts a 24×36 mm sensor of 22 megapixels, at a price of $8000 (body only); I won't even mention the weight, as it is obscene. This is the same pixel density as 5 MP on a Four Thirds frame. |

|

Native image size:

3648×2736 |

The aspect ratio, as in all Four Thirds cameras and almost all non-SLR ones is 4:3, as opposed to 3:2 in all other digital SLRs. Those inherited that ratio from the 35 mm film, where it emerged as a byproduct of the fact, that Mr. Barnack joined two 4:3 movie frames into a single 3:2 frame in his Leica prototype almost 100 years ago.

For most applications I prefer the 4:3 ratio which is generally more pleasing and fits better all standard print sizes larger than a postcard. For some landscapes we may prefer something more elongated, and for that even 3:2 is usually not enough. |

|

Color depth:

12 bits per RGB component |

Not changed from the previous models, the same as in most current cameras (except for some of the simplest models, which may use 10 bits per color (BPC). The full information is retained only if your image is saved in the raw format; in JPEGs it will be converted to When you view an image on the screen, the color depth, in all current display systems, is still limited to 8 BPC, regardless of how the image was saved. |

|

Capture sensitivity:

ISO 100 to 1600 in full EV increments |

This is another change from older Olympus models, where ISO settings above 400 were available only as an option, providing not quite the same image quality. The expanded ISO range is one of the most touted (and, possibly, most overrated) new features in the E-510 and E-410.

As I was able to check, the results at ISO 800 are quite good, and at ISO 1600 — usable; a performance similar to, or better than, that of the Canon 400D, whose high-ISO capabilities were by many seen as one of the biggest advantages of that camera (we'll come back to that in the Noise Suppression section). The E-510 allows to set the ISO only in full EV increments, i.e., 100, 200, etc., but not, for example, ISO 160. I do not consider it a limitation at all. If you think you can see a difference between ISO 200 and 250, you should be playing stock market big time, and not taking pictures. You can, however, set the upper limit to which the autoexposure logic will raise ISO if needed. This happens not only with flash, like in older Olympus cameras; obviously, they have more confidence in the high-ISO performance of the E-510. Additionally, one of the "scene modes" offers more aggressive ISO adjustments. |

|

Low-pass and anti-IR filter:

Non-removable |

The low-pass (or anti-aliasing) filter, commonly used in digital cameras, introduces some fuzziness to the image; this results in avoiding Moirè patterns, showing up on some regularly spaced detail. Obviously, this filter makes your pictures less sharp (that's why Leica got rid of it in their recent M8).

I suspect the E-510 (and E-410) may be using a less aggressive version of this filter tnan the previous models. This would allow the camera to take a better advantage of the lens resolution. My suspicion was prompted by the unusually high resolution of images with noise filtering off, see here. The infrared-blocking filter protects the sensor from capturing the IR light which negatively affects the image, especially color balance. This feature is also common. Both filters are placed just in front of the image sensor, and in some cameras they are combined into one. I'm not sure if that's the case in the E-510, but it wasn't in the E-500. |

|

Infrared sensitivity:

Exposure factor of 10 EV. |

The sensitivity of the E-510/E-410 to infrared seems to be the same (or, maybe, slightly higher) than that of the E-500 (recent version). With the R72 IR filter on your lens, an infrared exposure of a brightly sunlit scene will need about 10 EV (a factor of 1000×) more exposure than the same scene shot in visible light (without filter).

For example, if a normal, visible-light exposure required by a scene is 1/1000 s, an infrared version of the same subject will require 1 s at the same aperture and ISO setting. The Live View is useful in IR shooting: without it the filter would have to be put on immediately before the shutter is released, after the scene has been framed without it. For more on this subject see my separate article on E-510 in infrared. |

|

Dust removal:

Yes, ultrasonic.

|

When a particle of dust (or lint, or anything else) gets into the camera's mirror chamber, as it may happen while a lens is being changed, it may settle down on the sensor, or rather on the foremost filter in front of it. This will show as a dark speck in the recorded image. The speck will be usually out of focus (fuzzy), depending on the distance from that filter surface to the sensor proper, and also on the aperture at which the picture was taken. This is best visible in smooth, uniform areas, like a blue, clear sky.

Some people believe that dust or dirt on a lens surface (including the filter in front of the latter) may cause a similar effect; I've seen and heard this many times. This is not true, as anyone who paid any attention to a convex lens ray diagram shown during high school classes will be clearly aware of. Such impurities may only cause some general softening of the image, and quite many are needed for this effect to become noticeable. Olympus addresses the problem with their patented Supersonic Wave Filter (another moniker which means exactly nothing). In this solution, the dust barrier (see the diagram at left) seals the CCD in and vibrates for one second or so at a low-ultrasonic frequency of 25 kHz when the camera is turned on; most of the particles are shaken off and stick to an adhesive surface at the bottom of the mirror chamber. (The sticky strips have to be replaced by a service center every three years or so, according to Olympus, but this depends on a number of factors.) This system has proven itself in all previous E-System cameras, being the first one in the industry. Since then, Sony, Canon, and Pentax introduced similar solutions (in spite of Canon's initial comments that they do not really need one). According to the test by Róbert Irházy of PixInfo.com, the anti-dust system in Olympus SLRs leaves all three others in the dust, as the only one which really works. While I cannot verify Róbert's findings, in four years of using E-system cameras I never experienced the dust problem (had a visible spot once, but it went away after a few frames, probably shaken-off by the removal system). |

|

Sensor cleaning option:

Yes | Activated from one of the menus, this flips up the mirror, which will stay so until the camera is turned off, giving you access to the dust barrier in front of the CCD — if you really need to clean it (I don't think so, see above). |

|

Operating principle:

Body-based, moving sensor |

Olympus is the last major SLR maker to offer image stabilization in their SLR systems. At this moment, Canon and Nikon are using IS systems built into some of their lenses, while Pentax and Sony went for IS in SLR camera bodies (the concept originally developed by Minolta).

(Panasonic and Leica, with their so far limited Four Thirds offerings, use image-stabilized lenses branded as Leitz, which will also work on the E-510 with the body-based IS turned off.) In both kinds of systems the job is done by mechanically compensating the detected vibrations of the camera/lens axis so that the image remains steady on the sensor. In lens-based ones this is performed by moving a dedicated element group in the lens; in body-based systems — by moving the image sensor itself. Proponents of the lens-based solution claim it is easier to implement and can provide better results, tweaked to a particular lens; adherers of the other do not even have to point to the fact that their system can work with any lens mounted on the camera. The body-based image stabilization should not be confused with the so-called "digital image stabilization", which is not image stabilization at all, but an exposure program, increasing the ISO more aggressively at low light levels, to allow for faster shutter speeds and thus reducing the probability of camera shake. With that advantage, I have no doubt that body-based systems will prevail: that's what the market will demand, although for some time both kinds will co-exists, even within the same SLR family (although one will have to be disabled for the other to be used). I would expect Canon to have an SLR with body-based stabilization within three years. Activation of the system in the E-510 is easy: press the [IS] button and choose one of the two available IS modes:

I've checked only Mode 1 so far. How well does it work? |

E-510, IS off

E-510, IS on (Mode 1) Both images: F=150 mm, 1/15 s These are typical examples of my two series, 60 frames each; see text. |

To avoid basing my opinions on a casual impression, I've started from an informal test, 60 frames shot with IS and 60 without, all using a shutter speed of 1/15 s at the focal length of 150 mm (corresponding to 300 mm on a 35-mm frame camera). At this length, the generally recognized "safe" handheld speed is 1/300 s, so I was more than 4 EV (or a factor of 20×) below that. The results were quite dramatic: image stabilization increased the share of clearly "good" frames from 2 to 32 out of sixty, and the fraction of obviously "bad" ones dropped from 47 to zero. This leaves no doubt: image stabilization really works. This does not answer the most frequently asked (if not the best-phrased) question: by how much does the IS lower the safe handheld speed? While I've seen this one answered in a number of sources, I do not trust a single one of them, without being able to verify the testing method used and the statistical interpretation of results. Frankly, most of the numbers claimed (for any camera) seem to be just invented. It took me some time and effort to design and execute a more thorough experiment, described in detail in another article. My results clearly indicate that the gain depends on the focal length used: I ended up with 1 EV for 14 mm, 1.6 EV for 42 mm, and 2.2 EV for 150 mm (this corresponds to exposures longer by 2, 3, and 5 times, respectively). The outcome, however, may also depend on other factors: lens weight and balance, your shooting technique, and more. There is simply no single answer to this question, and I haven't yet seen any dependable numbers for any other camera, so my results cannot be compared with anything else. Olympus recommends disabling the IS when shooting from a tripod. My experience confirms a need for that: one of my series of 16 tripod-based frames, with the IS accidentally left on, seems visibly more fuzzy than when re-shot without IS. The results do not look visibly shaken (no smear or double contours) — just like if autofocus was working wrong. Again, I'm tempted to run a more formal test of that effect to get a better grip on its magnitude. Legacy lens support. (In the original version of this report, this paragraph opened from "Now the bad news"). In a recent (January, 2008) development Olympus released a firmware update allowing to use image stabilization with legacy lenses, with no electronic coupling to the camera body. When such a lens is installed on the camera, you have to dial in its focal length, so that the IS system will be aware of the nature of camera/lens shake to expect. I've checked this feature and it seems to be working just fine. At last. Note: Turning the camera off with the IS enabled, you will hear a sound with a camera shaking slightly with what seems like a 5 Hz frequency. This may sound alarming, but it is a normal behavior; Olympus must have needed it for some undisclosed purpose. |

White Balance:

Two pictures taken 18 seconds apart, with identical settings and under identical conditions. The only difference is a slightly different framing. This shows what may happen when you depend on Auto WB, especially with mixed light sources (fluorescent plus daylight). E-510, ISO 1600, 1/125 s at F/5.6. |

The white balance setting affects the perceived color in the generated images. While most people do not realize that, we do not want the colors to be recorded truthfully (like a living room scene being reddish because it is being illuminated by incandescent bulbs) — the human brain adjusts our perception, removing (most of) the prevailing color cast, and we expect the same from a camera.

Many photographers, not just beginners, leave the camera set to Auto, hoping this will do. This is not the best idea: the Auto WB will work reasonably well only if your picture contains a clear white (and not too small) area. Otherwise you're risking that the camera's decision will be less than optimal; you may also lose color consistency between consequent frames: a series of slightly differently framed pictures may end up with quite different WB settings, definitely not nice. (See the example at the left.) Using a stand-alone, incident light meter with color temperature option is generally the most accurate approach, but very few people (mostly professionals) do that. Some cameras (like the Olympus E-1) have an external light sensor to help in WB setting, but this is only a partial solution; if you want your pictures right, simply do not use the Auto WB option, regardless of camera. At least do not do it outdoors, where choosing between one of three available presets (see below) is really not a rocket science. To give you some say in WB of your pictures, Olympus (like most manufacturers) offers a number of presets, marking each with a mnemonic icon (when accessed from the menu system, all these are accompanied with the color temperature value in degrees Kelvin):

(The color temperature concept is not really applicable to fluorescent light, so the latter are "equivalent" values, but this is a technicality.) There is also one user-defined setting, to which you can assign any color temperature value (in 50°K increments) for a quick recall. Artificial light sources may differ strongly in color temperature; for example, a tungsten bulb may have a color temperature from 2000°K to 4000°K. Under such (and not only) conditions, a more precise way to set the white balance is by reference: letting the camera take a trial picture of a white or neutral-gray area, and to analyze it without saving to the memory card; the resulting WB estimate will then be stored in an easily accessible setting. This requires the [Fn], or Function, button to be assigned to Reference WB; the feature cannot be accessed otherwise (like, from example, from the menu). This feature worked very well on the previous E-System cameras, especially under incandescent light, as I was able to check both by a casual examination of results and by checking the RGB values in an image editor. The white balance settings are applied during the raw-to-RGB conversion of the captured image, therefore pictures saved in the raw format (ORF) are not affected. The measured WB, however, is stored in the header of an ORF file and can be applied when the raw file is converted to RGB on your computer. Each of the presets (including Auto and Reference, but not Custom) can be modified by applying additional corrections in two color planes (red/cyan and green/magenta). These adjustments are persistent: remembered when a preset is changed or the camera turned off. This is a way to customize your camera's color response to your liking. All corrections can be also set to a common value, or reset to zero in a single operation from the menu system. The adjustments have a range of ±7 steps of size unspecified by Olympus; this is not much of a problem, because you set them by trial and error anyway. |

|

WB bracketing:

Three steps each in two color planes; three or nine frames total. |

When this option is used, the camera takes just one exposure, but saves it as a number of JPEG files, applying various color corrections during the raw-to-JPEG conversion. Three files are saved if bracketing is applied to one dimension, nine — when to both (red/cyan and green/magenta). The magnitude of color shift between different versions can be set to 2, 4, or 6 "steps", presumably the same ones as those used in WB adjustment described above.

Strangely, this option is also available in the raw format, where the camera writes three or nine ORF files to the memory card. This is not smart at all: all these files contain identical raw image information, differing only in the WB information in the header. Generally, I find the WB bracketing function useless: it is faster to take one frame saved in the raw format and then try the various color adjustments in postprocessing. |

|

Noise suppression:

Yes, both static and random |

Noise in digital camera images is a sum of two components: static and random. If you are unfamiliar with the subject, refer to my noise article as a general introduction. The E-510, similarly to most SLRs addresses each component in a different way.

The static noise, predominant at long exposures under low light, is reduced by dark frame subtraction: immediately after the picture is taken, the camera records another frame at the same settings (ISO and exposure time), but without opening the shutter at all. That frame is then subtracted from the original one. This approach works quite well, especially, if not only, with the hot pixels (see, again, the article mentioned). Olympus refers to this as noise reduction. Because of the extra exposure of the same length as the original one, and extra processing involved, this feature takes an extra time before the camera is ready for the next picture. Time is not the only penalty for static noise reduction. The random component is increased in the process. This is why Olympus activates it only at long exposure times: 8 s and up at ISO 100, or 4 s and up at ISO 200 and above (don't try to find this in the manual). At faster speeds it will not kick in, even if set. As my test results with the E-500 indicate, the best solution would be to activate the noise reduction at a shutter time inversely proportional to the ISO value; this conclusion should also hold for the E-510. Interestingly, Olympus changed the way how the noise reduction works if the image is saved as a raw file. In previous models that file contained also the dark frame, to be subtracted only during the raw-to-RGB conversion in postprocessing, therefore it was larger. In the E-510, the file size is not affected by the process; it looks like it already contains the result of subtraction. The random noise occurs, with differing magnitudes, at all light levels, and all camera makers apply some filtering to smooth it out. A side-effect of the process is, unfortunately, some loss of image detail — although the filter algorithms make this not so obvious by trying to preserve line sharpness and/or applying some sharpening afterwards. What we end up with is an image with less noise, less detail, and relatively sharp contours. This is called noise filtering. What I like very much about the E-510 is that you can adjust its magnitude to your liking. While the setting is buried deep in the menu system, this is a very powerful feature, which I didn't realized until I tried it. I wish this setting could be assigned independently to (and memorized for) each ISO value, or, even better, to every combination of that value and image mode (Vivid, Natural, and Muted). This is only natural: image modes are digital equivalents of various film emulsions, and grain characteristics is an important signature of these. The sharpening degree is already assignable to individual image modes, so doing the same for noise filtering would be just a logical extension; these two are tightly related. Noise filtering can be set to one of four positions: Off, Low, Standard, and High; each of these has a different effect at different ISO settings, and the differences between the four are larger than I expected. Only after some extensive experimentation I realized how much is the image sharpness affected by noise filter setting. In this context I find the default Standard setting excessive at any ISO; my preference is Off for ISO 100 and 200, maybe even ISO 400, and Low above that (for full details see a separate article); this, unfortunately means that after changing ISO I have to dig into the menu system to adjust the noise filter — a cumbersome process. This decision by Olympus can be explained by a noise hysteria around the previous Olympus models. People who wouldn't tell a sharp image from a contrasty one would yell Noise! any time they saw any on a computer screen in a full pixel scale magnification, at the same time happy with blurred images from some other cameras (including the Digital Rebel). A noise and sharpness comparison between the E-510 and 400D can be found in a review at Digicam Review, and it is quite revealing. Only at ISO 1600 has the 400D a slight advantage of lower noise, at a heavy price in sharpness loss, visible at all ISO settings. These Digicam Review findings may raise some eyebrows, and I am not in a position to confirm or contradict them. They may, or may not, have something to do with lenses used — the Canon kit zoom, according to many, is of rather low quality; the article does not mention what lenses were used in the comparison. The DP Review includes a similar comparison in a review of the E-410 (which is image-wise identical to the E-510). This comparison, done with prime lenses, shows the Olympus noise a bit lower (including ISO 1600), but I can see the Canon images are (just a tad) sharper. The comparison, however, was done with noise filtering set to Standard, which makes it less meaningful; actually, this may not really contradict the results mentioned above. More, any noise comparisons based on the standard deviation of pixel luminance (and many I've seen use this metrics) are wrong and misleading. At high pixel counts, the noise uniformity (lack of autocorrelations) is more important than just its amplitude, as anyone familiar with fine-grained film will know. In either case, I do not think that the differences discussed are strong enough to be visible in 12×16" (30×40 cm) prints viewed from the "standard" distance equal to the print diagonal. All this said, I still think that the first thing a new user of the E-510 should do is to set noise filtering to Low at most, and start from there. Too bad most of them will never bother doing this. So, how is the noise in the E-510? Very well under control, thank you. It is tight and uniform, free of the chroma component (colored specs) prevailing in the older models, very low up to ISO 400 (even with noise filtering off), low at ISO 800, and moderate at ISO 1600 which becomes a useful option for available-light shooting. At longer (one second or so) ISO 1600 exposures, some images exhibit horizontal banding, a problem common to many digital SLRs. I have to investigate the matter further to say when this is most likely to occur, but this does not stop me from using this setting for handholdable shutter speeds (for which it is intended: if I have to use a tripod, I may as well go to ISO 100 anyway). |

|

Color space:

sRGB or Adobe RGB |

Adobe RGB can be used for better color rendition (wider gamut) with applications which can take advantage of it, especially for professional printing. I never had a need to use it.

The worst happens when an inexperienced user sets the color space to Adobe RGB without knowing why (just because it must be better!) and then views or edits the images with applications which are not set to use that. Advice: if you are not sure, leave this setting alone! |

Picture Modes:

|

I liked this option in the E-500, and I like it in the E-510; this is like defining four different imaging profiles (like different kinds of film) and then quickly choosing between them.

Too bad the manual does not say anything about these four choices except what anyone can figure out from the names. I find this offensive, but this is not my first issue with the Olympus publications department, and not the last one. Each of these four "films" may have a number of detailed settings assigned to it: contrast, sharpening, color saturation, and "gradation". The first three can be adjusted within ±2 notches, for the last one, see below, we have a choice of Normal, High Key, and Low Key (again, it would be better not to explain them at all in the manual, than keeping the explanations as they are). Once these settings are defined, they will stay attached to the given picture mode and recalled every time that mode is used. Very nice. The remaining picture mode is Monotone (which translates into English as "monochrome"). I was skeptical about its usability in the E-500, but I'm beginning to change my mind. Unless you write your images as ORF files, it may come handy, as it seems to give somewhat better results than saving a color JPEG and then converting it to monochrome, especially when used with a "color filter" option (see below), and especially in infrared. The monochrome mode skips the adjustments of saturation (obviously) and gradation (why? it should be perfectly applicable here), adding two others: color filter and image tint. The first option is similar (but not quite equivalent) to using a lens filter: none, yellow, orange, red, and green. The second allows the monochrome image to be slightly tinted in a number of hues (quite nicely chosen, by the way). Olympus removed the "sepia" mode (which was present in the E-500) realizing that it is nothing else than a tinted monochrome. They are right, that was just illogical. |

Image adjustment:

|

All these adjustments are applied during the raw-to-RGB conversion, so they are not essential if you save your images as ORF files (they are, however, stored in the ORF headers so that can be recalled during postprocessing).

As I mentioned before, these adjustments are set and memorized independently for each of the Picture Modes discussed above. What I am missing now in the E-510 is a possibility to attach also the noise filter setting to a picture mode. This would be perhaps my favorite feature, even at the expense of removing the "gradation" setting altogether. Another possible enhancement would be to assign the detailed image parameter set not just to the picture mode, but to its particular combination with sensor gain (ISO); after all, a contrast setting appropriate for ISO 100 may be not so good for ISO 400. This, however, is not as simple as my previous wish. |

Lens correction:

|

The light fall-off (or vignetting) is an effect seen, to a varying degree, mostly with wide-angle lenses, especially at full apertures. It demonstrates itself as gradual darkening of image corners. Some of it is due to the lens itself, some — to the directional response of the sensor.

A remedy for it is available as an option (disabled by default) in the E-510, accessible from the menu system as "Shading Compensation". (There is no such term like "shading" in the English photographic terminology; this is another example of the creative abuse of that language I cannot get used to.) Every Four Thirds lens transfers its fall-off characteristics to the camera, which then may compensate for the effect during raw-to-RGB conversion. (This means that images stored as raw files will not be affected, although they carry the information to be used in postprocessing, if so chosen.) If you use the Olympus Master or Studio software for postprocessing, you may postpone this step; it can be applied to both raw and JPEG files. The lens distortion, also most obvious at wider angles, can be corrected in a similar way, but in postprocessing only, based on the lens data embedded in the image file. It can be applied to raw or JPEG files. |

In-camera image editing

|

These functions can be applied to the picture which is being viewed. The raw-to-JPEG conversion applies the current camera settings (as opposed to those used at shooting), including the white balance, and saves the result as a new JPEG file. The other operations can be only performed on JPEG images.

I do not consider any of these functions really useful, therefore I'm not going to go into any detail here. |

Image file format:

|

The ORF files save the information as picked up from the CCD, without any processing. The individual signal values for red, green, and blue photosites are preserved, without being converted (interpolated in two out of three components) to RGB pixels.

For more on raw files, see my Raw Image Format article. For most practical purposes (including all I do), JPEG files are just fine. While that format uses compression in which some image detail is lost and some compression artifacts introduced, at low compression ratios these effects are really negligible. A new feature in the E-510 is that ORF files are compressed, using a lossless compression scheme. This reduces the file size: the "new" raw files are about 9-11 MB each, while the uncompressed ones in the E-500 were 13.6 MB in spite of smaller amount of information contained (8 megapixels as opposed to 10). In this camera, Olympus decided to drop the TIFF format support. It will not be missed at all. On the other hand, we are still waiting for the first camera manufacturer who would bite the bullet and support JPEG 2000, a superior format. |

|

JPEG compression:

1:2.7, 1:4, 1:8, and 1:12 |

These are nominal values; the actual compression ratio will vary from image to image.

The 1:2.7 (best quality) compression is practically lossless, better than most of us actually need, but it produces largest files. Usually I set my compression to 1:4 and this is more than good enough. Only for some test samples I turn to 1:2.7, but even this many be some overkill. Compression rates are not adjusted directly: they are assigned to image quality presets, and only the latter can be selected before a picture is taken. |

Average file size:

|

These values are quoted by Olympus; obviously, with a compression applied the final size will always depend on the particular image: those which less detail will compress better.

A simple experiment: take a picture from a tripod; then switch to manual focus and use it to get a really blurred picture. The second file will be visibly smaller than the first one, at least in the JPEG format. My experience shows that usually the averages will be 10-15% lower than those in the specs: about 6 MB for 1:2.7 and about 4 MB for 1:4; I didn't bother to check higher compressions. A hundred or so raw files I just looked at had sizes ranging from 8.6 to 11.4 megabytes, with most between 9 and 10 MB. Olympus compression ratios are usually lower (i.e., quality: higher) than for other makers. For example, the Canon 400D Fine and Standard modes generate file sizes similar to those at 1:4 and 1:8 on the E-510, respectively. |

Image size (pixels):

|

A wide choice, but do we really need it? Imagine taking a series of pictures saved as 1024×768 VGA files, intended for Internet use, and then discovering that some of them deserve being printed to a poster size. No chance to go back!

The only options which may be useful in some situations are the two largest non-native sizes, still printable in formats larger than a postcard; they can be used in an emergency, when we are running out of card space far from home. When one of the non-native format is used, the picture is being taken in full resolution, and the raw picture is being resized only in the process of being converted to RGB. It is unclear if the conversion is done straight to the reduced resolution, or with the intermediate stage of a the full-size RGB. While the latter is simpler to implement, the former may, theoretically at least, provide better results. But do we really care? |

Image quality presets:

|

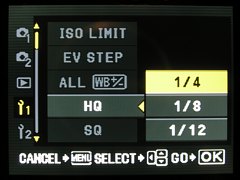

These, as explained above, are applicable only when images are saved in the JPEG format. The Control Panel allows you to choose between these three options (in addition to raw), but two of these can be pre-defined as combinations of pixel size and compression. Thus the presets are:

This is a setup used for a number of years in most Olympus cameras, and it reminds me of an indirect electoral system. While I don't like it too much, I can live with it. My advice is to set the HQ and SQ presets to your liking once and forever, and then use them as if they were hardwired. |

Meta-information stored:

|

The JPEG standard allows for a supplementary information (i.e. one which is not a part of the actual image) to be stored in the image file. Most of various camera's raw formats, ORF is this number, offer the same possibility. This is referred to as EXIF information.

Many popular image browsing or processing programs allow you to access the EXIF information, so does the Olympus Master included with the E-510. Unfortunately, most of these programs allow you only to see a part of it, not always the most important items. Well, the Olympus Master is actually one of the worst programs in this aspect, leaving out lots of interesting stuff. OK, so you know that the basic shooting information, like camera type, focal length, shutter, aperture, ISO, and white balance settings are stored as EXIF data, and most programs would display those items. But what about some other juicy morsels, like, just for example, focusing distance, dept-of-field-range, or body and lens serial numbers I was able to extract from E-510 files? I cannot see any explicit data on two interesting things: image stabilization and noise filtering. I suspect, however, that they are hidden among parameters cryptically named as, for example, Olympus Image Processing 0x0303. One day I'm going to find this information. We all know that many image files contain embedded thumbnails in the EXIF data; this is also the case here, and the thumbnail size is 120×160 pixels. It is not a common knowledge, however, that Olympus files (ORF or full-size JPEG type) also contain a smaller version of a JPEG, used for in-camera, magnified preview. This image is 1200×1600 pixels (approximately 2 MP). It is quite heavily compressed, usually to 300..400 kB, which gives a compression ratio of 1:15..1:20. |

Storage medium:

|

The camera has a two card slots, one for each type, and you can switch between them on the go. Although this solution does not offer much above a single card, somehow I like it — without a real reason.

Compact Flash, the oldest surviving standard (remember SmartMedia which once had more than 50% of the market?) still seems to offer most advantages, except for size, which may be too large for compact cameras. These cards have on-board controllers, which means that the increased performance of newer models can be more easily utilized on older cameras, in addition to fewer compatibility problems. With the now defunct SmartMedia, almost every increase in capacity required an update to camera's hardware, and those were not always released. Unfortunately, the situation with xD-Picture is similar (although not quite as bad). Compact Flash offers largest capacity, fastest writing speeds, best compatibility, and lowest prices, therefore the choice is a no-brainer. Still, to utilize the second slot I would suggest getting an xD-Picture card (the faster "H" type). You can use it when running out of CF space, or for backup of selected images from the Compact Flash (the camera offers such an option). The E-510 is capable of taking advantage of fast writing speeds of modern cards; the writing times are quite impressive. For example: storing an ORF file on a 2 GB SanDisk Extreme III takes about 1.3 seconds (JPEG takes approximately the same, as some time is used for raw-to-RGB conversion). The newer Extreme IV does not seem to offer visible advantages beyond that. For more on this see my article on card-writing speeds. |

|

Dual-format saving:

Yes, ORF+JPEG | I never had a need to use this feature, but some people may. Plus, it looks good on a specs checklist. |

|

Computer interface:

USB 2.0, storage-class device |

At long last, in this camera Olympus moved to the real USB 2.0 connection, officially referred to as USB 2.0 High Speed (as opposed to the Full Speed flavor, which is far from the full speed USB 2.0 is capable of).

The resulting increase in transfer rates is dramatic, as long as a fast card is being used. Transferring 150 JPEG image files (550 MB) from the E-510 using the Extreme III CF card to my cheap laptop took 102 seconds; the same files took 667 seconds when the card was plugged into my E-500. That's more than 5 MB per second, a speed increase by more than six times! Some sources quote transfer rates not in megabytes (MB/s) but in megabits per second, Mb/s (lowercase 'b'). 5 MB/s is the same as 40 Mb/s. I clocked a similar speedup (by a factor of 7×) on my three-year old desktop. Surprisingly, when I copied the same files to an Extreme IV card, the transfer rate went down by 10%, but such small differences may be due to different physical location of the files on the solid-state disk. I don't think this warrants any further investigation. |

|

Dual viewing:

|

In addition to optical, through-the-lens viewing, the E-510 adds a possibility to preview the scene as picked up from the imager, on the LCD monitor.

This is not intended as a replacement for the regular viewing mode, but rather as an option to be used only under circumstances when its advantages prevail above disadvantages. For a more detailed discussion of this viewing mode refer to the Live View section near the end of this article. The rest of the present viewfinder section will deal only with the SLR viewing. |

|

SLR viewing system:

Pentamirror and groundglass; 95% coverage; 0.92× magnification

Information shown:

|

The pentamirror is less expensive and weighs less, but provides a somewhat less bright image than a pentaprism. In practice, I wasn't able to see any difference between both, using the E-1 and E-300 side-by-side.

The focusing screen is not user-changeable. It has three AF point marks (with blinking confirmation LEDs) and a circle marking the center-weighted metering sensitivity region. As in the E-500, I find this circle useless and distractive, but this may be personal. The 95% coverage is defined, as customary, in linear terms, and it means that about 90% of image area (0.952) is shown. Camera makers prefer to quote a linear value without any explanation; if they were selling land, then 50% of a square mile would really mean 0.5×0.5 mile squared. The information shown to the right of the finder image is quite comprehensive, but, as in previous E-System models, it is difficult to see, especially for glass-wearers. The finder magnification, 0.92× is barely better (no noticeable difference) than in the E-500, perhaps one of the weakest points of this camera — but the finder is still usable, as long as you do not insist on manual focusing (and most people don't). This magnification, as specified by all digital camera makers (let me spare you the details how it is defined), is not a meaningful parameter when cameras of different sensor sizes are being compared. For comparability (showing all in terms of the 35-mm film frame), the quoted finder magnifications should be divided by the focal length multiplier (2 for Four Thirds, 1.62 for Canon, 1.53 for Nikon APS-C). Thus (putting the aspect ratio differences aside and speaking in terms of diagonal size), the "equivalent" finder magnification for the E-510 is 0.46× (0.92/2), for the Canon 400D it is 0.49× (or the quoted 0.8/1.62; slightly larger), and for the Nikon D40x — 0.52× (0.8/1.53). Now, the upcoming E-3 specifies finder magnification as 1.15×, which, after normalization, gives 0.57× — almost 25% more than in the E-510. (The image size differs even more because of the 100% coverage, not 95%). In a comical twist, Popular Photography uses a set of guidelines to convert finder magnification values to verbose descriptions. The problem is that they've never updated these to accommodate various frame sizes, and thus, for example, the 0.92× value for the E-510 is considered "excellent", while 0.8 for a Canon 400D — just "very good", both providing the same viewing experience equivalent to 0.5 on a 35-mm SLR; very poor. Still, the Canon model gets shortchanged in this snafu. I was hoping the E-510 will have a larger finder, but this did not happen. I understand that doubling the finder size reduces its brightness by a factor of four, but maybe a solution like that in the E-10/E-20 would work: increasing screen transparency at the expense of manual focus precision (your eye can adjust to the shift of the aerial image); after all, all people use the viewfinder for viewing, and only a few — for manual focusing. |

|

Diopter adjustment:

From -3 to +1 diopters | This is a typical range. The adjustment knob is quite crude in action, barely adequate. |

Other features:

|

The eyepiece cover should be used when your eye is not protecting the eyepiece from stray light: this affects light metering accuracy. In practice, I use it when the camera is mounted on a tripod, especially shooting in infrared.

Unfortunately, this small accessory has not been improved from previous models: a flimsy piece of plastic, easy to misplace. I'm not talking about an eyepiece shutter, activated with a small lever, like in more expensive cameras, but a smarter design of the existing eyepiece blind, attachable to the camera strap, would be a nice and cheap solution. The eyecup included with the camera is EP-5, good enough. If you wish, you can replace it with a larger EP-6. There is also a magnifying ME-1 eyecup available, enlarging the viewfinder image 1.2×. All these are described in a separate story. |

|

Depth-of-field preview:

Yes. |

Some SLR users like to preview the depth of field by closing the aperture down to the value set (by hand or by the autoexposure system). This is quite useful with larger finders available on full-frame cameras, less so with small ones like the one in the E-510.

Still, the camera provides this option, but at a price: you have to dedicate the sole assignable function button, [Fn], to activating it. You will be then unable to access other functions which also can be assigned to that button; for example, setting the white balance by reference. You can, of course, reassign the [Fn] button on the fly as you need it, but this is a cumbersome procedure, requiring a tedious search through the settings menus. Oh, well, I'm not bothered by this but you may be. |

|

Mirror lockup:

Yes: shutter delay |

To avoid camera vibrations caused by the mirror slap, you can set a delay between that (activated with the release button) and the actual shutter action. You may want to use this in critical tripod applications, but, frankly, I rarely bother. The delay can be set to any whole value between 1 and 30 seconds and has been hidden at the very bottom of one of the menus, right next to flash bracketing (where else?).

In yet another burst of linguistic creativity, Olympus documentation refers to mirror lock as Anti-Shock. |

|

Type:

Mechanical, focal-plane, electronic control | This is what all digital SLRs have. For a general information on this type of shutters, see my article here. |

| Speeds: 60 s – 1/4000 s, up to 8 minutes in bulb setting |

This is generous and, again, common to most digital SLRs. (Of the cameras I've tried only the Nikon D200 goes up to 1/8000 s). The long end of 60 seconds is more than in the competition (other current sub-$1000 models go to 30 s), but this is really of no importance. (Still, my 60-second, ISO 100 frames are beautifully rendered).

The whole range is available in all exposure modes, but at higher ISO settings they may exceed the autoexposure metering range, so you must know what you are doing. |

|

Max. flash synch speed:

1/180 s | This is the "official" value. In reality, you may often synchronize a (non-dedicated) flash up to 1/320 s, which I was able to check using a thyristor-automated flash from Adorama, and camera set to manual exposure mode. See the flash section for more. |

|

Release:

Soft-touch, electronic | The same as in previous models: no better, no worse. A bit too stiff for my taste (this increases the risk of camera shake). |

Modes available:

|

These are accessed with a dedicated button placed at the left of camera's top. The self-timer can be set to 2 or 10 seconds, and the IR remote delay — to 0 or 2 seconds.

The self-timer can be canceled by pressing the drive button again during the countdown. What I do not like is that there is no audible confirmation that it has been activated with the shutter release. I also believe the mirror should go up as soon as the release is pressed in the self timer mode. This would address my previous complaint, at the same time providing the functionality of mirror lock. The latter could be then removed from the menu system (simplifying it a bit), at the same time becoming accessible externally. I really do not need to set the lock delay to exactly 17 seconds; a choice between 2 and 12 is enough. Simpler is better. |

|

Sequential rate:

3 FPS up to 8 or more frames |

In the sequential drive mode the camera keeps taking pictures as long as the shutter release is kept pressed, or until the internal memory buffer gets full. In the latter case the rate will slow down do about one frame per second (or whatever it takes to write the image file, depending on the card used), but the shooting will continue. You can also start another sequence while the previous one is still being saved.

My informal tests has shown that I can get 10 or 11 raw frames within about 4.5 seconds, or 25 SHQ (1:2.7) JPEG ones in 9 seconds until the buffer fills up — a rate of about 2.5 FPS. At the compression of 1:4 I've given up after 60 frames in 19 seconds (3 FPS). The card used in this check was SandDisk Extreme IV, the fastest one I have at my disposal. These numbers are applicable to the Single AF mode, in which the autofocusing is done only at the first frame. In Continuous AF the camera re-focuses before each frame, so my clocked rate dropped to (almost exactly) 2 FPS, but the sequence length, in SHQ at least, increased (I didn't bother to check by how much). The rate may, of course, depend on focus conditions. The continuous shooting rates and sequence lengths are what I would expect from a camera in this class (for example, the Canon 400D gets up to 28 frames at 3 FPS in 1:4 compression). Anything faster calls for a pro model, with the appropriate price in terms of money and carrying weight. Or just consider buying a video camera.

|

|

Remote release:

|

Adding the wired remote option (RM-UC1, $50) at long last addressed one of my gripes about the E-500. It uses the USB/video socket in the camera's back and works just fine. Externally, the RM-UC1 looks exactly like the RM-CB1 for some other cameras; it even has a holder for the screw-on remote socket cover no longer present on cameras it works with.

Wireless remotes (RM-1 or RM-2) used to be included in the box with most of the Olympus cameras until about three years ago. They will both work with the E-510, but the $30 (RM-1) price is, to put it mildly, a rip-off. I'm glad I have like six of them around the house. The RM-1 also has zoom out/in buttons, which on the E-510 are used to open and close the shutter in the Bulb mode (RM-2 will not work at all in that setting). The Olympus Studio software ($100) allows you to access all settings (except for zoom), trigger the camera, and save images to the computer. It may be useful in studio or lab settings. |

|

Time-lapse sequences:

No | People, pleeez! What does it take to provide this feature, even if it is not of the first importance? It can be done entirely in firmware: take away the most useless features (scene mode "guide", DPOF printing, white balance bracketing), and give me this one, in case I need it one day... |

|

Light metering:

Full-aperture TTL, an array of 49 sensors |

Through-the-lens (TTL) metering at full aperture is a standard on all modern SLRs, digital or film. The E-510 uses a matrix of 49 (7×7) sensors to do that, measuring the light off the viewing screen.

The metering seems to be precise and consistent. Rumors about a tendency to underexpose or overexpose in the E-510 (I've seen both) arise, most probably, from the author's unfamiliarity with using autoexposure systems, especially in high-contrast situations; see also the next item. |

Metering modes:

|

ESP, or Electro-Sensitive Pattern is an Olympus' term used for all metering systems in their cameras for the last ten or twenty years, regardless of how these systems worked. It means nothing; another widespread industry practice, offending your intelligence. It really is a kind of matrix metering with a number of sensors measuring the light in different image areas; then some smart averaging algorithm comes up with the proper exposure.

Any exposure system can be fooled: the camera does not know what the photographer considers the best tonality for the image. Is this uniform area a sandy Caribbean beach, or a dark, volcanic beach in Costa Rica? How dark do you want it to be? Does this bright part contain some detail you want to preserve, or can you afford to have it rendered very high, maybe even burnt-out? Do professional photographers use external, incident-light meters because they are stupid and have too much money to burn, or, maybe, they have a reason not to trust the TTL metering of their (often expensive) cameras? This is why most cameras have an option of exposure compensation, and using it is the first photography skill a novice has to learn. Too bad many testers do not know this and often stick to "all-factory settings, no adjustments" policy of taking sample pictures. My preference is to keep the brightest parts of the image from running out of dynamic range; therefore I tend to use lowered contrast setting and a negative exposure compensation when the tonal range of the scene is wide but the brightest parts are too small to be properly recognized by the metering zones and/or algorithm. Usually I vary this compensation between -0.3 and -0.7 EV when using the matrix metering mode; possibly just a bit less than with the E-500. You can also switch (from the menu system only, why?) between a "regular" ESP metering mode, and the ESP+AF one, in which the averaging algorithm assigns greater weights to the matrix segments close to the point used to autofocus on. The center-weighted mode averages the image area brightness with weights falling off from the center out. This is a robust and predictable approach, a choice of many photographers, especially the film-era oldtimers. Frankly speaking, I'm not using it at all; maybe I should? Spot metering uses the information from the central 2% of the image area. An experienced user may get very good results from this approach, knowing where to point the spot (that area will be rendered at the standard 18% gray level). There are also two extra flavors of the spot metering mode: Highlight Spot and Shadow Spot. These will render the metered area as a highlight or a shadow, but it is unclear and undocumented at what level, so this can be learned only by experimentation. I've never felt any need for these options, preferring to use a regular spot mode plus exposure compensation, like in "I want this to be two steps above the standard 18% gray". This is faster, simpler, and most flexible. |

|

Metering range:

EV 1 to 20 in all metering modes (ISO 100, F/2.0 lens) |

This is not the most clear way to say what exposures the camera will be able to meter properly, although it allows for comparisons between various cameras: the wider the range in each direction, the better.

Simple arithmetic can be used to translate these specs to something more meaningful: Note that this does not mean that the E-510 can meter exposures only up to two seconds. For example, take the shorter "kit" zoom at the wide end, with the maximum aperture of F/3.5. Two seconds at that aperture is the same exposure as 80 seconds at F/22. Anyway, the metering range for the E-510 is similar to what other cameras in this class offer. |

Exposure control modes:

|

This is as expected from an SLR, which will be, on average, used by more experienced photographers than other camera types.

In the program mode the camera adjusts both the shutter speed and aperture. Olympus program modes (and many others) use the 45° line approach, modified to account for lens sharpness degradation occurring at smallest openings due to light diffraction. |

E-520 exposure program for an F/3.5 lens at F = 14 mm (Graph by Olympus)

The correct version is shown below.

E-620 exposure program for an F/3.5 lens at F = 14 mm (Graph by Olympus) This applies to the E-510 as well. |

This is shown as the dark line in the accompanying graph (modified from the User Manual). As the light level increases (EV numbers are shown next to diagonal lines), the shutter and aperture settings change as follows:

The program can be shifted towards faster or slower shutter speeds by turning the control wheel; the aperture will be adjusted to keep the exposure constant. This is shown in the graph as gray lines, for one negative and one positive shift value. Note that program shift also moves the horizontal line segment [3] up or down. While the graph does not show such a move for segment [1], shifting the program towards slower shutter speeds actually moves that part up. I've discovered that only when reviewing the E-620 in 2009, comparing both cameras side-by-side. I think I've checked this when originally reviewing the '510! Is it possible that this change in behavior was introduced in one of the firmware updates? In any case, the Olympus graph reproduced here no longer reflects the reality (for shifted program, that is). ANother opicture, reproduced from the E-620 manual, shows how things really are. I consider this feature not really useful: to gain more control over the shutter speed or aperture, it is better to switch to shutter or aperture priority. The program shift is activated with the control wheel alone, no buttons pressed. This can be easily done by accident. The shift is marked by a small 'S' next to the 'P' program symbol in the Control Panel, easy to miss. Once you discover the change and want to revert it, you will not know in which direction to turn the wheel, as the display shows neither the shift direction nor its magnitude. The fastest way is to leave and re-enter the program mode by turning the mode dial back and forth — clumsy. This is an example when an extra feature, looking good on paper, does more harm than good. You can assign the "bare" wheel functionality in program mode to exposure compensation. While it also can be accidentally modified, it is clearly visible and easy to adjust in the desired direction. The program shift is then no longer available. That's what I'm using on my cameras now. Aperture and shutter priority work as expected: you set one parameter and the camera adjusts the other. Time ("bulb") exposures allow for manual shutter timing up to 8 minutes: press the release button, and the shutter remains open as long as the button is kept pressed. While using the camer's shutter release in this contecxt does not make much sense, the button on the optional, wired RM-UC1 remote works the same way. The name itself goes back to the times when a photographer would open the shutter, manually fire a flash bulb (these were small bubbles filled with magnesia, single-use) and then close the shutter. The Auto setting is essentially the same as Program, except that it disables the program shift and reverts most of the settings to their defaults — still allowing you to modify them. The modifications, however, will last only until you leave the Auto mode, when the camera will revert to whatever you have set before entering it. Not having a need for the Auto mode, and without a clear description in the manual, I misunderstood the general principle behind it in the E-500. After getting deeper into the subject with the E-510 (in which it works the same way), I had to revisit my E-500 review and correct it. In the last three years I find myself doing 90% of my picture taking in the aperture priority mode, having moved from program after getting a better feel on what depth of field is provided by various apertures and focal lengths in the Four Thirds format. |

|

Specialized programs:

18 "scene modes" |

By setting the mode dial to Scene, you can use the LCD monitor to choose between one of the eighteen "scene modes", with plain English names and pre-packaged combinations of camera settings which the designers deemed as most useful in a given kind of shooting.

The selection process is accompanied by small example pictures and brief descriptions; for example: Portrait: For taking a portrait-style shot, or Children: Shooting active children. (No, I'm not inventing this!) In addition, some of these descriptions are unclear, like: Macro: Best for close-up pictures or Nature Macro: Best for close-up pictures of small objects. Assuming I've decided to use the "scene modes" — how do I choose between these two? To make things worse, Olympus never bothered with documenting what these presets actually do, but here, perhaps, they were right: people using them are very unlikely to read. I'm not going to discuss, or even list, the eighteen "scene modes"; you can find that in some other reviews and, if you are reading this, you are unlikely to need or use them. Let me only mention two, somewhat less trivial than others: