|

Olympus E-300, a Technical Review |

|

My other articles related to the |

|

The E-300 (called Evolt in the U.S., why?) is the first affordable digital SLR from Olympus, following in the footsteps of the E-1 of last year, of which I hold a high opinion.

Having owned both the E-10 and E-20 fixed-zoom SLRs and three high-end, non-SLR Olympus models, I grew to like the way in which Olympus designers make their compromises (if any camera maker says theirs don't make any, they are just lying). My three-year old E-20 is still working fine and delivers results adequate for most purposes I need, but it is quite slow (in saving, not shooting!), compared with current breed of cameras, therefore last November I was on a lookout for a new digital SLR. Being on a budget, I aimed at the price range below, say, $1200, and having no significant investment in film-SLR lenses (except for fifty or so in my Exakta collection, and a few Minolta ones), I was not restrained to a particular brand. A fellow E-20 user switched recently to a Canon 300D and is very happy with the new camera; he kindly offered to let me use it for a few days to try it out, along with 18-55 and 70-200 mm zoom lenses. To make a long story short, after having spent three days with the Canon 300D I decided against buying it. While most of the time the results were very good (except for occasional color problems), I didn't like the feel of the camera (not just ergonomics), and found some of the designed-in limitations, most of them imposed by the firmware, irritating. (Don't ask me to go into details; this would require writing a review and I'm not up for that. If you want to see a Canon-trashing review, go to almost any Nikon fan site, and vice versa.) Well, this may be a matter of taste, and while I consider the 300D a good buy (especially for the money), this is not a camera for me. All the time since its release I was tempted with the Olympus E-1, but not quite ready to spend this kind of money; I also found it a bit too large and too heavy for my taste. Therefore, hoping for the best, I decided to try the E-300 out as soon as it becomes available in the United States. (Besides, a friend overseas wanted to get one too: he offered to buy it from me if I decided not to keep it, as the U.S. price is much lower than what he would have to pay. A no-risk situation.) So on December 14, 2004 I got my E-300 and started the process of trying it out, at the same time writing this review (started a month earlier as an annotated specs sheet). It has been updated many times since and still is occasionally maintained. Note: with one exception, all other digital cameras I bought and kept were made by Olympus. Therefore you may suspect me of a pro-Olympus bias. Sometimes I ask myself this question, too. My choices, however, were not based on "brand loyalty" (in which I don't believe); to the contrary, I'm at odds with Olympus on a number of issues, and in the past I returned two of their cameras I considered not acceptable (no names, please). |

| Body | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Construction:

|

Olympus says the body frame is sturdy enough to handle all 4/3 lenses, including the 300 mm (600 mm EFL) big gun.

The top cover looks like either a bold fashion statement, or an afterthought, depending on your attitude. I'll have to get used to it. The absence of the pentaprism hump above the lens reinforces the unusual look (note: even many digital-finder cameras have an imitation prism hump, to make them look more like SLRs). While the look is high-tech, I don't like it too much. For the time being, the distinction of best looks among digital SLRs belongs to the Pentax *ist DS, I think. In particular, the flat-top appearance can be considered nice or ugly, depending on your taste, attitude, and the day of the week. Regardless of that, the camera looks and feels more "serious" than others in its class. By the way, the body is made in China. This made me a bit suspicious at first (stereotypes?), but only the label gives that away, not the construction or finish quality. A first-rate job here. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Finish and feel:

Black, with warm-hued aluminum top cover, rubberized grip. |

The finish is first-class; no corner-cutting in this department. Actually, the crinkled plastic body feels like metal in my E-20, while the aluminum top might be confused with plastic (if not for being colder to the touch).

The camera is easy to hold securely (in spite of being left-side-heavy); the rubberized hand grip and thumb rest are of the right size and shape, yielding to the touch with the kind of feeling I like. The E-300 certainly feels better than and not as cheap as the competing models, especially the Canon 300D Digital Rebel. At least from the outside you wouldn't guess this is an economy model. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Weatherproofing:

None | Don't expect this in a digital SLR at this price, at least not yet. In some promotional materials Olympus refers to the E-300 as dust-proof, bit I'm not sure what exactly does that mean. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Size (WxHxD):

146×85×64 mm |

While this is not small, the camera has a smaller height than any other digital SLR. It is, however, wider than many of the competition. Compared to the E-1, it is 5 mm wider, 19 mm shorter, and 17 mm less deep.

If the camera width could have been reduced by 15 mm or so, the proportions would be better, and the size more enjoyable. For sure, this is not a size revolution like that of the famous OM-1; we have to wait a few more years for that. One would think that the Four Thirds standard, with the image size being half of that in 35-mm cameras, would allow for smaller cameras. Not so: the E-300 (not to mention the E-1) is still larger than any full-frame, 35-mm SLR, excluding some heavy-weight, pro-grade models. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Weight (body):

580 g |

85 g less than the E-1, or just 20 g more than the Canon Digital Rebel. If you have a '5050 or '5060, keep it as a traveling-light camera (and for some other uses where they may be more convenient, like tabletop or infrared photography).

Together with the bundled 14-45 mm zoom the camera weighs 865 g. This is almost 200 g less than the E-20, a noticeable, if not dramatic, difference. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Interchangeable lenses:

Four Thirds standard

Zuiko Digital 40-150 mm F/3.5-4.5

|

All 4/3 lenses, originally released for the E-1, will work with the E-300. This is a good news, as those are optically very good (which, unfortunately, is reflected in prices).

Because this is an open standard, with well-documented interfaces and specs, we should see more third-party lenses for the E-300, more aggressively priced. At this moment Sigma already has three models. Generally speaking, I would divide the available lenses for the 4/3 system into four price categories, correlated with specs and quality: cheap (up to $200), moderate (up to $500), expensive (up to $1000), and exotic (beyond). So far only two zooms by Sigma fit into the first category, while the second one includes another Sigma zoom, two mid-range zooms from Olympus and, barely, the 14-54 mm F/2.8-3.5 introduced with the E-1. The expensive group has two Olympus zooms with attractive focal length ranges of 11-22 mm and 50-200 mm, and with wide apertures of F/2.8-3.5. Finally, the exotic division consists of two prime (non-zoom) lenses of professional grade and prices to match: a 150/2.0 ($2500) and a 300/2.8 ($7000). I doubt Olympus sells many of these, but they play an important role of presenting the E-System as meeting the needs of the most demanding users. For reference, have a look at the full, current 4/3 lens list. As I've already mentioned, most of the 4/3 lenses by Olympus are quite expensive, but the 40-150 mm F/3.5-4.5 (shown at left), aimed at E-300 users, sells at $280. The image quality of this lens is surprisingly good; adding it to the bundled 14-45 mm will cover the 35-mm equivalent focal length range from 28 mm to 300 mm. OM lens adapter: On some markets and at some times Olympus offers, upon request, a free adapter allowing you to use Olympus OM-series lenses on E-system cameras. Do not ask me, check the Olympus user support. If not given away, it is sold at the outrageous price of $200. For more on this, see here. Other adapters are available for other types of lenses. Obviously, you can use non-4/3 lenses only in manual or aperture priority mode, with stepped-down metering. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Mount size:

46 mm internal diameter

(Picture by Olympus) |

The bayonet is large — larger than many 35-mm bayonets, in spite of the fact that the 4/3 system sensor is half size (linear) of a film frame. This precludes making 4/3 cameras much smaller in the future.

The picture shows how big the lens mount is, as compared with the body. You can also see the electric contacts to pass the information to and from the body. The viewing screen is positioned vertically, immediately to the right of the mirror, but hidden beyond the mount flange and not visible in the picture. The bayonet action is smooth, precise, and positive, not a cheap job. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Control coupling:

Electronic |

The information exchanged between lens and camera is not limited to the obvious, like aperture or focal length; data on light fall-off and geometrical distortion is also changing hands, so that it can be used to correct these flaws. (More on this — see the Image Processing section).

As a matter of fact, 4/3 lenses have their own computer chips with the embedded firmware, which can be updated from the camera. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Standard lens:

14-45, F/3.5-5.6 zoom

The 14-45 mm zoom bundled with the E-300.

|

Initially the E-300 is being sold only bundled with this lens, which is the "economy version" of the excellent 14-54, F/2.8-3.5 zoom bundled with the E-1. "Economy" means here "half-price", making the lens (or the bundle) affordable to us the Joneses.

Judging from my results, the lens is a good performer. In designing this lens Olympus made the right choice, putting optical performance ahead of the (relatively modest) specs. The 14-45 mm focal length range (equivalent to 28-90 mm on a 35-mm camera) is more useful than one starting at 35 or even 38 mm, often encountered in the specs-driven electronic finder cameras. A 3× zoom starting from 28 mm EFL is more difficult and more expensive to make than a 5× one starting at 35 mm (which might be better received by some segments of the market). The aperture closes down to F/22; at this frame size this is not trivial. While F/11 would be adequate for general shooting (and cheaper to make), F/22 comes useful in close-up applications, a nice thing. On the downside, the lens is quite dark: F/3.5 at the wide end, and F/5.6 at the long end; this is a 1.36 EV difference. This affects not only exposure, but also the brightness of the image in the viewfinder. The compromise has its reasons. Among the four variables: focal length range, maximum aperture, optical quality, and price, you can adjust almost arbitrarily any two; with some difficulty and extra limitations — three, but never four, period. And Olympus got it right in this case. The make and finish of the lens (also made in China) are OK, with the zoom mechanism providing the right feel and precision. While it does not ooze quality like its more expensive counterpart, it is far from feeling cheap. The front element does not rotate when you zoom or change focus (important when you use a polarizing filter), but zooming is not internal: the inner barrel slides in and out of the outer one in a cam-driven action. This is why I would advice against using any lens attachments heavier than 100-150 g (4-6 oz). The zooming is mechanical, while focusing, done via a ring on the lens, uses electronic coupling. I was never enthusiastic about the latter feature, but it widely used by all makers, perhaps being less expensive. This lens (and its 40-150 mm "economy" sibling) does not offer a distance scale, which is present on all mid- and up-range 4/3 lenses from Olympus. Once again, an economy measure, but I can easily live with this. It's a pity you cannot (as of December, 2004) buy the E-300 body alone. I would be quite willing to pay $300 extra to get the 14-52 mm lens, not really for a greater focal length range, but for a brighter viewing image and faster shutter speeds. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sensor type:

Full Frame Transfer CCD: KAF-8300CE by Kodak

|

The chip is made in Rochester, NY (buy American!); you can see the specs sheet (for really nitty-gritty details refer to the PDF document referenced there). In particular the chip's dynamic range is a respectable 64.4 dB (compared to the excellent 67 dB of the KAF-5101CE used in the E-1), and its resistance to blooming (purple fringing) should be equally good.

In full-frame transfer CCDs all connecting circuitry runs in a layer beneath the photosites (light-sensitive elements), not alongside. This means that the photosites themselves may occupy almost all surface of the chip, with a greater effective light-collecting size. The image quality may potentially be improved this way, with less noise and not only. These chips require a real, mechanical shutter to define exposure times (electronic switching, or "gating" does not work with them), but this is not a problem with mid- to high-end cameras which all have mechanical shutters anyway. Those interested should have a look at the detailed and interesting discussion of the KAF-8300CE by Jason Busch at digitaldingus.com. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Effective sensor size:

17.3×13.0 mm |

This is the size corresponding to the actual recorded image; the total sensitive area is 18.0×13.5 mm, with the margins used for other purposes.

I have read some complaints about how much is this smaller than the APS size used in other digital SLRs. Let's check the numbers. The Canon EOS 20D chip is 22.5×15 mm. Some of the longer dimension is wasted anyway: of common print formats only 4×6" (10×15 cm) has a 3:2 aspect ratio capable of using the full 3:2 frame; most others are closer to the 4:3 ratio, like the "small" exhibition size of 30×40 cm (12×16"). Thus, the 20D suddenly becomes a 7MP (not 8MP, as 1 MP has to be cropped out) camera, with the usable chip size of 20×15 mm; the linear difference is only 15.5%. Hardly a big deal; and taking into account the full-frame transfer chip in the Olympus, the actual photosite size may the same or larger in Olympus models than in APS-sized ones at the same resolution. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Pixel count:

Nominal 8 megapixels, or 7.62 "binary" MP |

Although the Kodak chip has a total of more than eight megapixels (or, more exactly, photosites interpolated into pixels), the exact number of those which end up within the recorded image is 7,990,272. I'm referring to this number as 7.62 MP: while "mega" means in science one million, in computer applications it traditionally denotes the factor 220, or 1,048,576, a difference of almost 5%.

Why all this hair-splitting? First, I'm addressing my articles to Readers who like to know such things, second, it simplifies the calculations. An uncompressed image from a 7.62 MP camera, with 8 bits (one byte) per color, will contain 3×7.62 = 22.86 MB of information. Now, is this a progress from the 5 MP of the E-1? Not necessarily, and for many reasons. Generally, the current technology (and, to some extent, the laws of physics) defines some pixel count above which, for a given sensor size, there is little, if any, additional gain in image quality. I would guess this limit, for the 4/3 sensor size, is somewhere between 5 and 8 MP. The 6 MP lower-end cameras already crossed this line (with the mass market being largely ignorant, and following the "more is better" marketing ploy). Yes, I would like to see a 20 MP camera, but only with the full 24×36 mm (or larger) frame size. On the other hand, 8 MP is 60% more than 5 MP, and this translates into an almost 30% increase in linear pixel resolution (square root of 1.6 minus one). Whether your pictures need that increase, and whether the camera is capable of using it (with the lens being possibly a bottleneck) is often hotly debated. My personal feeling is that same-sized prints (of, say, 12×16 inches or 30×40 cm) from the 5 MP E-1 are as good as those from the E-300 in terms of perceived sharpness. Still, 30% more of linear resolution is nothing to sniff at, and better lenses can take advantage of this. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Native image size:

3264×2448 |

Yes, that's the digital-standard 4:3 aspect ratio.

I consider this important: so far all SLRs by other makers follow the traditional film proportions of 3:2. When printed on any standard paper size except for the smallest 4×6" (10×15 cm), those cameras waste about 15% of their pixels, not to mention that the image composition may be also impacted or even ruined. How come nobody mentions that? I'm using an SLR largely because of the accuracy in framing and composition, and I like framing my subjects tight. I don't want to keep guessing how the results will be affected by cutting 15% off the image width. This takes precedence above many other factors relentlessly discussed by the pixel-counting crowd. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Color depth:

12 bits per RGB component |

Except for the E-1, offering 14 bits per color (BPC), previous Olympus cameras used 10 BPC; the two extra bits effectively extend the dynamic range in each color component by a factor of four. (This refers to the range captured by the sensor and digitized, before being saved to the image file, keep on reading.)

Greater color depth, potentially at least, allows us more flexibility in squeezing the image tonal range into the 8 BPC depth of most formats used for final images (JPEG, TIFF), helping to extract extra detail from highlights or shadows. The full 12 BPC information, obviously, will be retained only if your image is saved in the raw ORF format, see below. Otherwise it is up to the in-camera circuitry to use the extra bits wisely in the conversion to 8 BPC. (JPEG bits are assigned with use of a logarithmic scale, so there is no loss of dynamic range, but granularity problems remain.) Being able to save the image in one of the "deeper" non-proprietary formats (16 BPC JPEG 2000 or TIFF) would allow the photographer to take full advantage of the captured information, without necessitating use of any ORF conversion software. Unfortunately, all camera makers are still ignoring this option. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Capture sensitivity:

|

Interestingly, Olympus no longer sees a need for the ISO settings below 100; they must have grown more confident in their noise levels; adding ISO 800 and 1600 also seems to support that.

To make the two highest settings available, you have to activate an option in the Setup menu. This is a sign that the maker considers them less acceptable than others. Still, I prefer a noisy picture to no picture at all, and high grain was always a fact of life in available-light photography. It is possible that, like in some other cameras, the settings beyond ISO 400 do not actually change the CCD gain, being implemented only in image conversion. In any case, don't expect miracles at the highest ISO values. Generally, I find all settings from ISO 100 to 400 good enough for any purposes, and even ISO 800 OK for low-light uses. ISO 1600, however, is very noisy, and usually will require s good noise removal program applied in postprocessing. For more on this, refer to my image samples and noise removal articles. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

IR-blocking filter:

Yes, non-removable |

All digital cameras require this filter, as the sensors used have a significant sensitivity to infrared, which adversely affects image color and tonality. As far as I know, only some Sony models allow this filter to be removed from the optical path, therefore making the cameras really useful for infrared photography.

In some cameras this filter is combined with the low-pass one, used to add a little "fuzziness" do the image, to reduce the possibility of Moiré patterns; in the E-300 it may be also combined with the dust protector, but it is unclear if it really is. Anyway, this, and the mechanical constraints, make the anti-IR filter removal unfeasible. Infrared sensitivity: My IR session with the E-300 shows that the exposure compensation factor when shooting with the infrared Hoya R-72 filter is about only about 7 EV — a surprisingly high infrared sensitivity! More, the IR images are less noisy than those from other Olympus cameras I've tried (E-10, E-20, C-5050Z, C-5060WZ). This means that, in spite of the lack of live image preview (missing in all digital SLRs except of E-10/E-20), the E-300 can be quite useful in IR photography. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dust removal:

Yes, ultrasonic |

This approach is exclusive to the E-1 and E-300, patented by Olympus and creatively referred to as "Supersonic Wave Filter" (it is not supersonic, and it is not a wave filter; another meaningless blurb).

When activated, it uses ultrasonic (25 kHz) vibrations to shake most of pollution particle types off the dust barrier (or low-pass filter), catching them (hopefully) on a sticky surface in the mirror chamber. This is important. Imagine every single speck of dust from your every film frame showing up on all your next frames as well, accumulating over time, and you will see what I mean. Or check the plethora of dust-removing sticky swabs, blowers, brushes, voodoo sticks and prayer beads, used with all other (interchangeable-lens) SLRs; this is what was making me hold on to my fixed-lens E-20, hoping that some day someone will come up with a kind of a solution. Well, Olympus did. The value of 25 kHz is a correction of the 350 kHz one which I originally posted repeating a piece of information quoted in one of other reviews. The correction follows the statement of Mr. Masaharu Hamada of the BCT R&D Department in an interview published at the E-Fotografija Web site in October, 2004. Based on my initial experiences and a few reports I've received from E-1 and E-300 users, the ultrasound dust removal really works, although I would still limit exposing the mirror chamber to elements to minimum, and in the cleanest possible conditions. Update of September, 2005: My monthly checks of clear blue sky frames have yet to reveal the first dust speck over the imager, and I'm switching between lenses quite often. The system really seems to work! It remains unclear how often do you have to send the camera to Olympus to have the sticky tape replaced, though. The dust shake-off is activated for a second or so every time the camera is turned on. For better efficiency of the process, the camera should be in the normal upright position at that time. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sensor cleaning option:

Yes, from the menu system |

The Cleaning Mode option in the Settings 2 menu flips the mirror to the side, opens the shutter, and freezes the camera in this state until it is powered off. This makes the dust barrier accessible for cleaning. I hope it will not be needed often, certainly not as often as with digital SLRs of other makers, missing the dust removal feature.

At least two reviews I've seen say that the Cleaning Mode activates the ultrasound dust shake-off process. An obvious mistake. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

White Balance:

|

In previous Olympus cameras the auto white balance worked generally fine, except for household incandescent light, under which the image was still not compensated for the red shift. My trials indicate that the E-300 is no worse in this area.

The presets include incandescent light (3000K and 3600K), fluorescent (4000K, 4500K, 6600K), sunny (5300K), cloudy (6000K), and open shade (7000K). I am happy to see, at last, each preset marked with both the corresponding symbol and the color temperature; no big deal, but it took Olympus a few years. Better late than never. The reference WB setting was originally introduced by Olympus in the E-10, but it begun to work properly only in the C-5050Z. This is done by pointing the camera towards a neutral (white or gray) surface and telling the camera (from the menu, that is): "this is what I consider neutral, white or gray". In the '5050 and '5060 this worked very well, giving best results under tricky conditions. On the E-10/E-20 and E-1 the feature has its own, dedicated button at camera's front; but, unfortunately, not on the E-300, one of first signs that this is an economy model. (You can assign the reference WB to the customized OK button, but this, for a number of reasons, is not as good.) Four user-defined settings can be adjusted manually between 2000K and 10000K in a number of discrete increments. Unfortunately, the captured reference WB cannot be entered into one of these slots. You could do it in C-5050Z and C-5060WZ, and I found it very useful (for example, setting up two different, metered presets for tabletop photography). The E-1 has four reference WB memory slots, too. The absence of this option in the E-300 is really a shame, as the feature can be implemented entirely in software. Setting the white balance by reference causes the camera to actually take a picture, and then analyze it in order to come up with the right setting. At first is seems a bit strange, but when you look at this closer, it isn't: how else can you do it in an SLR, where the CCD itself is used to process the information?) Another omission is the external white balance sensor. Roughly speaking, this sensor (present in the C-5060WZ and in E-1) allows the camera to tell if a scene is red because the object itself reflects red wavelengths, or because the light used to illuminate the object is red. In the latter case the color balance should be corrected towards cyan, in the former — it shouldn't. This looks like some corner-cutting again, but I'm not sure if and how it will affect real-life results. (This is not just the cost of the sensor: to use it, the camera needs a second, independent, color temperature readout circuitry.) Note of May, 2005: While in most cases the auto WB in the E-300 delivers very good results, I have noticed occasional problems when images shot outdoors with large amounts of green are overcompensated into magenta. Sometimes I see this effect in just one frame of otherwise almost identical shots taken within a few seconds from each other: quite a random behavior and quite difficult to understand (a consistent overcompensation would be easier to explain). This happens even after I've upgraded to the Version 1.2 of camera's firmware, and I've never seen this behavior in other Olympus cameras I have used extensively in the past (C-3000Z, C-5050Z, C-5060WZ, C-60, E-10, E-20), except maybe, to some extent, in the E-1. As I said, this happens quite rarely, but it can be quite annoying. I hope another firmware upgrade will address the problem — it is hard to believe Olympus is not aware of it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

WB adjustments:

±7 steps in 20K (?) increments |

Those adjustments can be applied individually to any of the presets (including user-defined ones), and will be recalled when that preset is used.

The adjustment increment is my guess: I suspect the step to be the same as in the E-1; larger changes can be done by just switching to the next preset. (The camera's Advanced Manual is not advanced enough to bother us with things we'll never be able to understand.) Instead of marking the corrections in degrees Kelvin, Olympus uses these steps (of undocumented value), and does it in a quite confusing way. Applying a positive correction of say, +5 steps to a setting of 3000K gives, as a result, the white balance of 2900K. Yes, I know, for some historical reasons a positive step means "make it more blue", but this is counter-intuitive: add 5 steps of 20 to 3000 to get 2900! | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

WB bracketing:

Three frames, 50K, 100K, or 150K apart |

The WB bracketing step can be set to one of these three values. I don't find much use for this feature: this magnitude of adjustment is easy to apply in postprocessing.

Note that the camera does not actually take three pictures here; just one, and then it applies three color corrections to three saved files. Therefore this has no real practical advantage; it may be aimed at those reviewers who evaluate cameras by counting tick marks in a feature list. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Noise reduction:

Yes, both static and random |

The static noise (including hot pixels) is handled by subtracting a "dark frame" from the original recorded image, very much like in many other cameras. This works very well for hot pixels, somewhat less for the lower-amplitude component. When you activate this feature from the menu, the camera will actually use it for exposures of four seconds and longer, where it actually makes a difference. See my E-300 dark noise analysis for more on this.

In most cameras, the random noise (occurring at all exposure levels) is filtered out at the stage of converting the raw photosite readings into pixels. All cameras do it. This is always a tricky process, regardless of how smart the filtering algorithms are, and you can always find a subject on which it will result in loss of detail. While Olympus claims to be using an "improved" dynamic denoising algorithm, I'm still skeptical. This is also why I'm not paying much attention to any camera noise measurements, as they can only show the noise after that filtering, without any regard to the lost image detail. The E-1 has an additional random noise filtering feature, using another, more advanced, algorithm, turned on from the menu system and incurring a cost: extra processing time. In the E-300 this option is not available. For a general introduction to noise issues, refer to my Noise in Digital Cameras article. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Color space:

|

This defines how the colors are represented by a mixture of three basic components.

According to what I've read, the Adobe RGB color space is capable of capturing a wider range of colors than sRGB. As the translation into a color space takes place when raw image is being converted into RGB (JPEG, TIFF), the choice is irrelevant when you save images in the raw mode (ORF files); you can postpone the decision until the conversion is done in postprocessing. Once that is done, however, any subsequent conversions will not bring any improvement: once information is lost, it is lost. The only time when I experienced (with my previous cameras, that is) visible problems with sRGB color representation was when shooting some flowers, especially in shades of deep violet and purple. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Image adjustment:

|

We have learned to expect saturation, sharpness and contrast adjustments to the process of converting raw image data into an RGB pixel field. All three are included here, each in a ±2 step range from the default (with the steps being whatever the designers chose).

The E-300 is missing an option to boost an individual color component, neither has it the "skin tones" preset (both present on the E-1). New in the E-300 (and E-1) is image tonal gradation adjustment: normal, high-key, or low-key. Olympus is not really specific about how this is really achieved, but I would imagine that this adjustment lifts or lowers the middle of the tonal response curve, therefore moving the midtones up or down without changing the limits of the tonal range. This may be a nice addition to available image adjustments, but I haven't use it much, preferring to do it in postprocessing. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lens correction:

|

Introducing these two in the E-1, Olympus caught the competition with their pants down, really.

The Four Thirds lenses, in addition to the usual, expected data, provide the camera with their characteristics regarding these two flaws, especially hard to avoid at short focal lengths (wide angles). I can bet this information is passed either as an interpolation table (linear magnification or light loss as a function of radial distance), or as a set of polynomial coefficients; both ways would serve the purpose just fine (actually, for lens vignetting the data has to be aperture-specific). This information can be then used to "reconstruct" the right image. For light fall-off it can be done simply by applying a multiplicative correction to pixel brightness; for geometric distortion — by moving the computed RGB values for a given photosite to a different pixel, along a radial line. Simple and ingenious. The geometric distortion correction is not available in the camera, you have to use the optional Olympus Studio software ($150) to use this feature; the included Olympus Master does not include it. I have tried it and, indeed, it works well, adjusting the degree to the focal length as needed; it works both with raw ORF and JPEG image files. Note of April 20, 2004: While the originally shipped firmware did not allow for light fall-off correction in-camera, Version 1.2 does (it can be activated from the menu system as "shading compensation"). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Image file format:

|

Images stored as ORF files retain all original information captured by the camera, without applying any adjustments, and without interpolating the photosite output values to RGP pixel components. Therefore you may treat ORF files as digital negatives, before any darkroom work is done.

This may be the safest way to store your pictures for critical applications. In real life, however, I found that saving images as low-compression JPEGs is all I need most of the time; I have yet to grow as a photographer to really need the raw storage option. I'm wondering when camera makers will start using the JPEG2000 (.jp2) format, which has better image quality at the same compression rate (or higher compression rate at the same quality). The format has been around for a while, and all better image processing or cataloging programs support it; I think it is time. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Special effects:

Black and white, sepia | This can be applied while shooting (but also in in-camera image-editing, see below). Anyway, I prefer to do it in postprocessing, having more control. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Image editing | The E-300 offers rudimentary editing of raw images: resizing and conversion to monochrome. I consider this a feature of tertiary usability: doing it in postprocessing gives you more options. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Image dimensions (pixels):

|

The non-native resolutions are available only for files saved in the JPEG image format.

The 320×400 pixel size puzzles me a bit. Why not just the full size, just 2% larger in each dimension? See also Storage and Data Transfer below. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Storage medium:

Compact Flash Type I or II |

In spite of all attempts to unseat it, the CF standard became predominant in digital cameras, at least those which can accommodate this card size. Notice that Olympus gave up (as it did already in the E-1) the two-slot option.

The camera will recognize the FAT32 file system, which makes it usable with cards of more than 2GB capacity. (As I don't have a card with more than 2 GB, I'm not sure if the camera also does FAT32 formatting.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

JPEG Compression:

1:8, 1:4, or 1:2.7 |

A good choice. The 1:2.7 compression ratio is hard to tell apart from TIFF, even under a close scrutiny. 1:4 is good enough for all but really critical applications (for which I would use ORF anyway), and 1:8 is just fine for most uses.

A native-size image (7.62 MP, see above) compressed to a JPEG will be written as a file of about 2.9, 5.7, or 8.5 MB (assuming the compression factors are as specified by the manufacturer). This varies from one image to another anyway, depending on the amount of detail. On average, I'm getting slightly higher compression ratios than these shown here. It should be noted that Olympus traditionally uses lower JPEG compression ratios (higher quality) than most of the competition. For example, Canon 20D (7.81 MP) compresses JPEGs down to about 3.6 MB ("fine", 1:6.5) and 1.8 MB ("normal", 1:13). While this may speed up the camera operation, some people may find these values a bit too high. The TIFF files remain uncompressed (although there is a lossless compressed TIFF format in existence), using about 23 MB per image. Actually, with full-information raw ORF on one side and low-compression JPEG on the other, I don't see a need for this format.

Olympus raw format is, contrary to what I thought before and to what most reviews say, uncompressed. As only one color component per pixel (really: photosite) needs to be saved, ORF files are still much smaller than TIFFs. The raw file size is 13.4 MB 7.62 MP (7,998,272 pixels) with two bytes (one color only!) per pixel means 15.24 MB; if, however with bit packing (which is not compression!), there will be just 1.5 bytes/pixel, i.e. 11.43 MB. Add to this any overhead information, and 13 MB makes perfect sense. Besides, compressed files would vary in size, at least a little. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Quality settings:

|

This, of course, refers only to the JPEG format. In a somewhat strange approach, compression ratios, as discussed above, and image dimensions (in pixels) are first assigned (see below) to three quality settings, and only then the photographer chooses in which setting images are saved. I find it confusing and unnecessary.

Switching between these three settings is fast; it requires the usual button-plus-wheel routine. The compression/size combinations are assigned to these settings as pre-defined or user-defined:

Actually, the first two settings are redundant, as they may be reproduced in the SQ mode, described below. Olympus included them to "simplify" the choice, but I don't see much simplification here, unless you set HQ and SQ combinations once and forever to your liking, and then only choose between the three options. Although this is better than in previous Olympus cameras (the system in the C-3030Z was really bad!), I hope one day Olympus will just introduce two separate, easily accessible, settings: image size and compression. Setting the format in one place and defining it in another is not really a good approach. My suggestion: set the HQ to full-size 1:4, SQ to 3200×2400 1:8, and forget about the whole confusion. Just switch between these three settings. (As I already mentioned, why is the full size not available in the SQ mode, but just 2% less in each dimension?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Dual-format saving:

Yes, ORF+JPEG |

This option allows you to save, in addition to the raw ORF file, a processed JPEG (SQ, HQ, or SHQ as described above).

The use, if any, of this feature will depend on your workflow. For example, one may imagine a photographer recording raw ORF files for publication, but also writing high-compression VGA versions to be emailed from a PDA to the editor as soon as the card is removed from the camera. Or a scenario where a lazy photographer (like myself) saves ORF files plus HQ JPEGs, but then keeps ORFs only for frames which need more than just a minor touch-up. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Uploading interfaces:

USB 1.1, storage-class device |

Olympus follows the misleading procedure introduced in the USB 2.0 specifications and also used by other manufacturers, referring to this as "Full Speed USB 2.0". Regardless of naming, this really is USB 1.1 at 12 Mb/s (or 1.5 MB/s). I suspect this is not much less than the camera/card combination can handle, so it shouldn't make much difference.

The USB port is, like in all other Olympus cameras I've used, hidden under a rubber door at the left-hand side of the camera body. The door is made slightly differently than in other models, and attaching an USB cable to the camera becomes quite inconvenient. A minor, but quite irritating quirk. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Optical viewing:

SLR, using Porro prism and groundglass

|

Do what you may, but nothing beats SLR viewing. It is, however, not free — and not just in terms of manufacturing costs and mechanical complexity; it also precludes live electronic preview, which may come handy in some situations. (Unless, of course, you use a beam-splitting mirror or prism, like in the E-10 or E-20.)

This said, Olympus surprised us by using a unique, side-swinging mirror in the E-300. This unusual design (used, I think, only once before: in the Olympus Pen half-frame in the 1960's) allows the designers to move the finder away from above the lens, therefore reducing the overall height of the camera. The downside is one more mirror in the viewing optical path. This also means that the eyepiece is not directly above the lens, but at the left end of the camera body. Right-eyed photographers (a majority) will find this useful: the camera is easier to hold and your nose does not press against the LCD monitor. Small pleasures of life. As an economy measure (with an added benefit of weight reduction), the viewing system does not have a traditional pentaprism, using a system of mirrors instead (sometimes referred to as Porro prisms, which is not quite the same in this case). One of the first things I did was to compare the viewfinder with that of my old E-20. Surprise: the finder in the older camera is larger and much brighter (the latter, no doubt, due to larger lens aperture, but remember that in the E-20 only a part of the incoming light is used for viewing). Still, the finder in the E-300 is quite usable with the included zoom lens (better with brighter lenses), and as good as finders in Canon 300D and Nikon D70, or in the E-1 (which was a surprise). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Focusing screens:

Non-interchangeable. | This simplifies many things. The matte screen installed in the E-300 has a central circle and three autofocus marks (with the active focusing point flashing red). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Depth-of-field preview:

Yes |

This feature has been included, I suspect, just to satisfy the reviewers. With the small viewfinder image in digital cameras (see below) I doubt the DOF preview can be really useful.

There is no separate button dedicated to this function (the E-1 has one), but the OK button on the back can be customized to do that. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Coverage:

94% width and height, 88% area |

Decent, better than in many film SLRs, but I would prefer 100% (like in the E-1). The current value means that I can't see 12% of the final image area. If you crop your images tight (as I do), this makes a difference.

These data are as published by Olympus. My own averaged measurements, performed at F=32 mm, are very close to 93% in each dimension, with accuracy better than 0.5%, which gives 86% area coverage. Close enough. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Image magnification:

100% at F=50 mm, infinity |

This may, at the first glance, look good for those who remember the olden days with SLRs providing a 100% magnification at 58 mm (which was the reason why that focal length became quite common). Modern, popular SLRs show some corner-cutting, and values of 70%-80% are more often used.

To compare the viewfinder image size against a 35-mm film SLR it would be more honest to use the same EFL (equivalent focal length); in those terms the E-300 can claim 50% at EFL=50 mm. To quote the Ladies' Man of Saturday Night Live: this is really small. The Canon 300D claims a magnification of 80%, and the Nikon D-70 — 75%, both at F=50 mm again. These numbers may look not as good, but divide them by proper focal length multipliers (1.6 and 1.5, respectively), and in both cases you arrive to 50% — your viewed image magnification, at the same lens angle, is exactly the same in all three cameras. Using the same method (actual, not equivalent, focal length), the finder in my old E-20 (with image just slightly larger) would have to be described as having a magnification of about 220% at F=50 mm, and finders of video cameras with a 4-mm sensor could boast a magnification of 1000% or more, while still providing a tunnel vision. This clearly demonstrates how misleading specs can be if they are misused, and in this case they are. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Diopter adjustment:

From -3 to +1 diopters | Thank you on behalf of all middle-aged men out there. The adjustment knob is very well placed: easy to reach with your eye at the finder, yet difficult to move by accident. Actually, I find it better than in the E-1. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Finder information:

|

This is lots of information, but all of it is crowded in a narrow text column to the right of the viewscreen. Some people may like this arrangement, others, especially, but not only, glass-wearers, would have preferred the display to be below the viewing area.

I am in the second group: wearing glasses, I'm unable to see the information display without moving my eye to the left. Update of September, 2005: After nine months of using the camera I can barely remember that the information display is there at all. Usually I don't see the display, and I do not bother to peek to the side to do it. I consider this to be a really bad design, perhaps my most severe misgiving about the E-300 ergonomics. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eye relief:

20 mm |

This value is supposed to say how close to the finder eyepiece does your eye have to be to see the whole viewed area. I'm unsure, however, how exactly it is defined, and whether various manufacturers use a standard method to measure it. Until I know that, this is just one more number, not really meaningful.

Eyeglass wearers will be able to see the whole viewed area without a problem, but not the information display next to it — see above. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mirror lockup: Yes. |

This feature has been added in Version 1.2 of the camera's firmware. From the menu system you can set the time interval between the mirror and shutter activation to anything between 1 and 20 seconds.

With smaller size and weight of the E-300 mirror (area and weight four times less while camera's total weight remains the same) this feature is less important than in a 35-mm SLR; still, it can be useful in critical work, protecting you from camera shake caused by shutter release action and mirror movement. For reasons unknown, Olympus refers to this feature as "anti-shake" instead of using the generally accepted term "mirror lockup". The term can be confused by some buyers with anti-shake mechanism of some lenses from other makers' systems. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other features:

|

The EP-3 eyecup (or rather eyeglass protector) is supplied with the camera. I found it quite disappointing, being just a piece of rubber, pushed onto the eyepiece mount in a clumsy fashion, instead of sliding over the mount. Clearly, an economy model. It works just fine, though, if you do not have to remove it.

The E-1 interchangeable eyecups do not fit the E-300. The accessory VA-1 angle finder can be used (with a special adapter), handy for tabletop photography. The E-300 does not have an internal eyepiece shutter. Instead, you can use an external eyepiece cover (EP-4, supplied), mounted in place of the eyecup, which has to be removed (see the remark above). Worse, the cover cannot be attached to the camera strap (a solution used in many film SLRs); you have to carry it separately. Providing a better (slide-on) eyecup would cost Olympus 15-20 cents; a strap-attachable cover, nothing (just a different plastic mold). Boo. If you never shoot from a tripod, fine: you will not see a difference. I thought, however, that the E-300 is aimed at a somewhat more demanding user. For me (infrared photography) an eyepiece shutter, or at least a better cover, would be a lifesaver. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Type:

Mechanical, focal-plane, electronic control |

This type of shutter is what we grew used to, accustomed to 35-mm SLRs, although it is not the only possible solution (see my lengthy discussion of this in the E-1 write-up). Still, everyone else is using focal-plane shutters on digital SLRs, so this may be the best compromise.

The shutter travels vertically (i.e. along the shorter dimension of the image). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speeds: 30s - 1/4000s, bulb |

The top speed of 1/4000 s is very good. Times longer than one second are rather for bragging rights than for actual, frequent use, but they do not cost anything to implement, so why not.

At this frame size and at 1/4000 s, the shutter slit width is just 0.6 mm, the same as in a 35-mm camera with a vertical shutter at 1/8000 s. It would be quite challenging to narrow the slit even further, still providing the required accuracy. On the other hand, faster speeds could be implemented by increasing curtain travel speed, see below. On the opposite end, the longest available shutter speed depends on the exposure automation mode, lens used, and the ISO setting.

The bulb setting allows for exposures of up to 8 minutes. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Max. flash synch speed:

1/180 s |

This is the longest exposure at which there is a time instant when the whole sensor is open to the light at the same time (and that's exactly when the flash fires). Reducing this time further would require increasing the speed with which the shutter curtains move across the frame. This is not impossible: because of the smaller frame size, the curtains in the E-300 move as fast as those in 35-mm SLRs with maximum synch speed of 1/90 s, hardly a big deal. Therefore I will not be surprised if one of the next E-System SLRs will offer flash synchronization at 1/400s or so.

Some dedicated Olympus flash units allow to use faster speeds with flash; see the Flash section below. Actually, my tests show proper synchronization with a non-dedicated flash (or, using the wording from the Advanced Manual, a "non-specified" one) up to 1/300s or so: just a trace of image cut-off at 1/320, and none at all at 1/250 s). | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Release:

Soft-touch, electronic | Not as soft and precise as on the E-10/E-20, but good enough. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Modes available:

Single, sequential | As expected. In a nice touch, the camera allows you to set the AF regimen (single or continuous) to be preset individually for each of these modes. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Sequential rate:

2.5 FPS up to 4 or more frames |

This frame rate is for the single AF mode, when the camera focuses only at the first shot of the series. In the continuous AF mode I clocked the E-300 at about 1 FPS, understandable with the need for re-focusing between frames.

The four-frame maximum holds in ORF, TIFF, and full-size JPEG formats compressed at 1:2.7 and 1:4. At the compression of 1:8 the camera will keep up with your shooting until the card is full. Similarly, reducing resolution to 5 MP you can shoot 15 frames or so with the 1:4 compression. Not too shabby. Most of the people complaining about the E-300 sequential mode, comparing it against Canon 350D and Nikon D50 forget that the 1:8 (worst-quality) compression ratio on this camera is less (better quality) than "Normal" settings on competing models. Besides, at this shooting speed I would rather worry about focusing than JPEG compression artifacts. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Buffer capacity:

64 MB |

This is the value which limits the number of sequential shots discussed above.

64 MB is no longer as impressive as it was just a few years ago: fast memory is getting cheaper every month. The E-1 has a 128 MB buffer. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Self-timer:

Yes, 2 or 12 seconds | Same as in other Olympus (and not only) models. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Remote release:

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

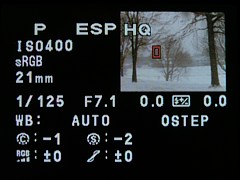

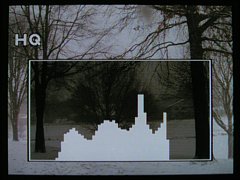

| Three out of six image playback modes. | ||

|

Magnification:

Yes, up to 10× |

The magnification up to ten times is useful in judging the sharpness of images.

At 10× the selected fragment of the image is shown in 74% of actual pixel size (already accounting for the misleading "pixel" count, see above), so if it is out of focus, you will be able to see that, although not so clearly. Increasing the monitor resolution would make this a really useful feature.

You can scroll through the image while it is magnified, and pressing the [INFO] button shows the full view with the enlarged fragment marked, very much like in image samples I'm showing. |

|

Index display:

4, 9, or 16 frames | As expected; set from the menu. |

|

Other modes:

Camera status display

|

While in the shooting mode, pressing the [INFO] button brings up a "Control Panel", offering a complete (or almost complete) display of camera's picture-taking settings. Changes to those settings can be made while this display is active, and some users, myself included, may prefer this way of operation.

It may be a subjective issue, but I find the Control Panel on the E-300 less readable than that on the C-5050Z and C-5060WZ. The black and white on blue display is not as clear as the almost-gray one on those cameras, and the text also seems to be not as crisp. Why mess with something which worked just fine? Update of February, 2005: After two months with the camera, I've got used to this display, but I still don't like it, compared to the "old" one. |

|

Video output:

PAL and NTSC | The TV output is switchable between both standards. Remember, however, that it does not provide real-time viewing (this is true for all current digital SLRs, where the sensor is not exposed to the light until the picture is actually taken). |

|

Generally, the controls on the E-300 look like they evolved from those on the E-1 (and, indirectly, the E-10/E-20). This is a good thing, as the E-1 handles well. The bad news is that in a few cases the changes from the E-10/E-20 are not improvements. The first impression in handling the camera is that the control layout, while quite good, but not as good as that in the E-10/E-20. I would say that even the less expensive, non-SLR models by Olympus, C-5050Z and C-5060WZ, have somewhat better ergonomics. This does not mean that the E-300 is bad in this aspect; I like it more than the Canon or Nikon models in this price range (and perhaps beyond).

| One new thing is a vertical row of buttons to the left of the LCD monitor; actually, they have been moved there mostly from the left-hand side of older Olympus models. For some users this may make accessing some functions less intuitive, as the button location becomes less unique. On the other hand, most of competing models use the same approach and nobody seems to complain. (Picture by Olympus)

|

| Another noticeable difference is the absence of the monochrome (low-power) LCD control panel on camera top (the one included on the E-1 was very nice). Its functionality has been taken over by the "Control Panel" display on the TFT monitor. I thought I would be missing the top display, which used to provide a visual feedback to the basic (but not all) adjustments. Actually, this is not the case. Pressing the Info button brings up the Control Panel as described above, and all adjustments are reflected there while they take place. As in most of the upper-tier Olympus cameras, the controls are adjusted using the press-and-turn approach: pressing a button selects the setting, and turning the control thumbwheel changes its value. Actually, this has been slightly modified in the E-300: you do not have to keep the button pressed, the camera offers you a brief "grace period" in which you have to start to turn the wheel if you let the button go. This is more important than it may seem, as in this model Olympus uses also the arrow buttons for the selection, and holding one down while turning the wheel would not be too convenient: both are located at the right of the camera's back. The grace period allows me to use my right thumb for both parts of the operation. Note of September, 2005: Version 1.3 of the firmware (last July) allow you to set this "grace period" to 2 or 5 seconds, or to infinity. While the wheel is being turned, the camera provides a visual feedback on the monitor screen: a small window with the value being adjusted. The monitor activates itself automatically if it was off before the operation, and turns off again after a second or so of wheel inactivity. This largely replaces the functionality of the top-deck LCD, but there is no indication in which direction to turn the wheel; for non-numeric entries I often find myself going through the full cycle, while a single step in the opposite direction would be enough. This works differently if you do the turn-and-press operation while the Control Panel is used to show all camera settings. In this case, pressing the button highlights the setting, and turning the wheel changes the value without removing the whole Control Panel off the screen. I like this mode of operation, because I can have the whole camera status at a glance; this reduces the danger of using some non-standard setting, forgetting to reset it, and then applying it to other shots without being aware of it. Note of April, 2005: After five months of using the camera I can say that the wheel itself is a little too easy to move accidentally (in the program mode this would lead to unintended program shift). Having it partially covered and/or moved to the left would be better. All this said, I find the control buttons in the E-300 not as precise and positive as those in the E-10/E-20 and E-1. Nothing bad, bot not the same feel. The menu system is called to the monitor screen by pressing of a dedicated button. The menu organization and readability are, I believe, a step back from the '5050/5060: the fonts are less readable, and the blue background does not help. I also have some issues with the menu structure. There are five menus: two for picture-taking adjustments, one for display, and two for general setup. The assignment of particular functions to these five is not always obvious, and sometimes — counter-intuitive; too often I find myself scrolling through the settings of one shooting menu only to find that what I need is in the other one. Additionally, for no apparent reason, there is no consistency in the interface: some menu entries, when activated, offer a choice from a submenu, while others call the same single-value window as the one used in thumbwheel operations, except that now you adjust the values using the up- and down-arrow keys. I was trying to find some regularity in using one or the other approach, but the designer's choice seems to be quite arbitrary here. I find the menu system somewhat less polished than in the previous Olympus models I've used. This is possibly a sign that the camera was rushed to the market to meet the Christmas shopping deadline. My biggest complaint is that flash exposure compensation is available only from the menu system (no dedicated button or other external control). This is one adjustment I use often when shooting outdoors with fill-in flash, and I would be happy to have it more easily accessible, even at the expense of some other adjustment. (No, the customized OK button cannot be assigned to this function, even if not needed for any other purpose.) I'm also not quite happy with the location of the OK button. After using the cursor keys, pressing it usually requires a repositioning of the camera in your hands. This did not seem to be a problem when I was learning the E-300 in the first few days with it, but the inconvenience seems to grow as you become more used to the camera. Of course, the controls are a highly subjective issue, so treat my opinions here as possibly tainted by personal likes and preferences. My general impression, however is that while the control system in the E-300 is quite good, it is not as good as I have expected, and not quite as good as in the other higher-end Olympus cameras I have experience with. My E-300 image sample page contains some images which may give you an idea of the image quality from this camera. Generally, I can say I'm mighty pleased with its performance, even with the bundled zoom lens. To those who may object to such unscientific terms: for me photography is a way to get "mighty pleased" with the results. With a background in physics and some hands-on experience in instrument optics I can read MTF plots, and I know how to do spectral analysis of noise. Still, a partial or incompetent use of hard data is worse than no use at all. As the bottom line, either I like the final results or not, and my results are pictures, not Fourier frequencies. Whether you may agree or not, at least read this article by Ken Rockwell, both informational and entertaining. First of all, the "economy" lens seems to be optically good enough in the whole focal length range. There is no objectionable softening of image in corners (just a tad at wide angle), no objectionable chromatic aberration. At the widest angle the zoom shows an average degree of spherical aberration (barrel), more at close distances; not impressive, but not bad. Wide open, it also has a slight vignetting at all focal lengths, which will not be objectionable in most situations, but in some it will. By "good enough" I mean good for most of I'm doing, including prints up to 30×40 cm (12×16"), although at this size I would rather use the lens slightly stepped down, to improve resolution and remove vignetting. If you want a better lens, go for the 14-54, F/2.8-3.5 zoom, which sells for $450-500. Well, you get what you pay for, there is no way to outsmart the system! The Kodak imager performs well: the dynamic range seems OK, and I had problems finding any traces of purple fringing around high-contrast transitions. (I have seen some chromatic aberration, but this is a different effect, due to the lens optics exclusively.) The colors are usually as good as I have learned to expect from Olympus: eye candy (in the good sense of the word). Contrary to my expectations the E-300 provides a better and more consistent automatic white balance than E-1, verified by shooting with both side-by-side; this in spite of the E-1 having an additional, external WB sensor. Now to the not-so-good news. Similar to some other recent Olympus (and not only) cameras, I believe the default in-camera sharpening is too strong: I can find white "bounces" at some high-contrast lines. This is a common problem with mass-market cameras, designed to impress a casual user performing a casual image inspection, and the E-300 is not as bad as many non-SLR cameras I've seen, but still. Setting the in-camera image sharpening to minimum (-2) brings this to an acceptable range. (I was quite surprised to see some reviews suggesting juts the opposite, but I stick to my opinion here.) Another complaint: the dynamic denoising algorithms (not to be confused with the "noise filter on the E-1) are also set, I believe, too aggressively. This can be seen in some grass areas, where the process can remove image detail, leading to a fuzzy effect. Again, the market is to blame for this (along with the camera maker), more willing to accept these artifacts than any noise in large, smooth areas of the image. Unfortunately, the aggressiveness of the noise filter cannot be controlled in camera or in raw image processing in the Olympus Master. (It is, I believe, adjustable in the Olympus Studio, if you have a $150 to spare.) I think this problem can (and should be) addressed in a firmware update. A hotly debated issue is that of the noise at ISO 800 and 1600. True: while ISO 800 is usable, if not spectacular, ISO 1600 — barely so, preferably with a noise-removal program. Still, we are talking ISO 1600 here, a really dim available-light shooting, not something I would need often. Note of September, 2005: There is also the elusive problem with the Green/Magenta shift, showing rarely but unexpectedly, and difficult to reproduce, as already described in the Image Processing section. It happens rarely, but when it does, it is ugly. I don't see it lately: was it fixed in Version 1.3 of the firmware? The bottom line is that, complaints aside, the overall image quality is very good, enough to satisfy a semi-serious user like myself, and even a serious one. In addition to the Quick Start poster, the box contains a printed copy of the Advanced Manual (in the U.S. three copies: English, French, and Spanish, but none in the U.K.; I'm not sure about other countries). This is (in the States, at least) a welcome departure from the Olympus' recent policy of providing the full manual only on a CD, but it doesn't take an Einstein to figure out that this is what the buyers want. Advanced Manual is really a misnomer: Basic Manual would be a better name for this well laid-out and nicely printed booklet of about 200 pages. The booklet is slightly larger than the previous ones; a good balance between portability and readability. Regarding the contents, I never had a high opinion of Olympus documentation, and this is no exception. I have to admit that the quality of the writing and coverage is improving from year to year, but still not enough. The language of the English version is better than before (with some room to improve, and remember that English is only my second language!), but the coverage still remains shallow and sometimes misleading. The major problem is that Olympus does not seem to believe that anyone with IQ above 80 and any experience in photography will ever buy the E-300. The manual contains very few things you wouldn't be able to figure out by just playing with the camera, while it lacks answers to many questions a photographer may ask about it. More, because the meaningful pieces of information are few and far between, they are easy to miss when our reading of the manual becomes just a casual glancing through the text which brings nothing of interest. On the brighter side: some of the passages are quite entertaining. Let me just quote one example: "The advanced shooting techniques used by professional photographers are drawn from years of experience. Now [...] you'll be able to take advantage of those same [sic!] advanced techniques simply by pressing a few buttons." Poor professional photographers, having wasted all those years instead of just spending $1000 to buy this camera. This will never happen again. Staying in line with the long tradition of the Camedia Master (of which the Olympus Master is a slightly modified version, the program is still disappointing. Still, you may need to install it on your computer for any of the following reasons:

In EXIF data readout, the Olympus Master does a better job than any general-use programs, I've tried, like ACDSee or Photo-Paint, which leave out or misinterpret some of the information. As a general image management or editing application, however, Olympus Master does not stand up to many entry-level applications. For more, see a separate, brief review. Every major player in the digital camera field (except for Sony, who is not really a traditional camera maker) has at least one model competing directly (or almost so) against the E-300. Well, with the recent price drop, even the Olympus' own E-1 competes against its younger sibling. The cameras Olympus is competing against feature- and price-wise are Canon 300D (a.k.a. Digital Rebel), Nikon D70, and Pentax *ist DS. From the samples I've seen, all three are capable of good results. All have bodies priced below $1000, with the Rebel being least expensive of the bunch (unfortunately, it shows). (Yes, I checked out the Canon 350D a.k.a. Digital Rebel XT, improved upon the original, but I'm still not impressed.) Two best cameras in the $1500 price range seem to be, at least in my subjective view, the Canon EOS 20D (finally Canon got almost everything right!), and Olympus' own E-1, not necessarily in this order. They are, however, more expensive than E-300. The Maxxum 7D by Konica Minolta is too new to tell if Minolta broke its stretch of disappointing cameras with attractive specs (for the record: I'm a long-time enthusiast of their film SLRs), it is also selling at $1500 for the body alone. Still, I've tried the controls, and I like them a lot, more than on any other camera from any maker, and certainly more than in the 20D. If you are reading this section in search of an advice which of the inexpensive digital SLRs I would recommend, you'll be disappointed. Most probably, every one of the cameras I've mentioned will deliver very good results, and your tastes and preferences may play a bigger role than any "objective" differences in cameras' specs and performance. This is a good camera, even better considering the price (April 2005: you can get the E-300 with the 14-45 mm lens at less than $750 from a respectable seller). After trying it out, I decided to keep it (and I have to get another one for my friend; he still wants one). What I like about it is the general image quality, the solidness of construction, and wide range of adjustments available. The controls are OK — not as good as in the E-10/E-20, but still. My biggest problem is with the placement of the viewfinder data display. I also wish the camera's width were 15 mm or so less. On the image quality front, my complaints about excessive dynamic noise filtering and the occasional Green/Magenta shift should not obscure the fact that images from the E-30 are usually very, very good. Most importantly, we have to see the camera compared to others in the same price range. I believe this one offers more than the competing models mentioned above, although my direct field experience with those is limited only to the Canon 300D/350D. If you are a happy Canon, Nikon, or Pentax user, especially with an investment in lenses, I will not try to persuade you away from sticking to that brand. If, however, you are an aspiring amateur without such a commitment, then I can easily recommend the E-300 as an excellent choice you will not regret. As always, the popular digital photography news and reviews sites offer detailed looks at the E-300:

Other reviews worth your attention are listed below:

Most importantly, there are Web sites run by dedicated amateurs (like myself), with a wealth of information. At this moment I can point you to one:

| ||

|

My other articles related to the |

|

Evolt® and Olympus® are registered trademarks of Olympus Corporation.

This page is not sponsored or endorsed by Olympus (or anyone else) and presents solely the views of the author. |

| Home: wrotniak.net | Search this site | Change font size |

| Posted 2004/11/16; last updated 2007/08/13; cleaned up 2013/11/18 | Copyright © 2004-2007 by J. Andrzej Wrotniak |